Exploring The Spectacular Chaos Of Mutiny In Heaven: The Birthday Party

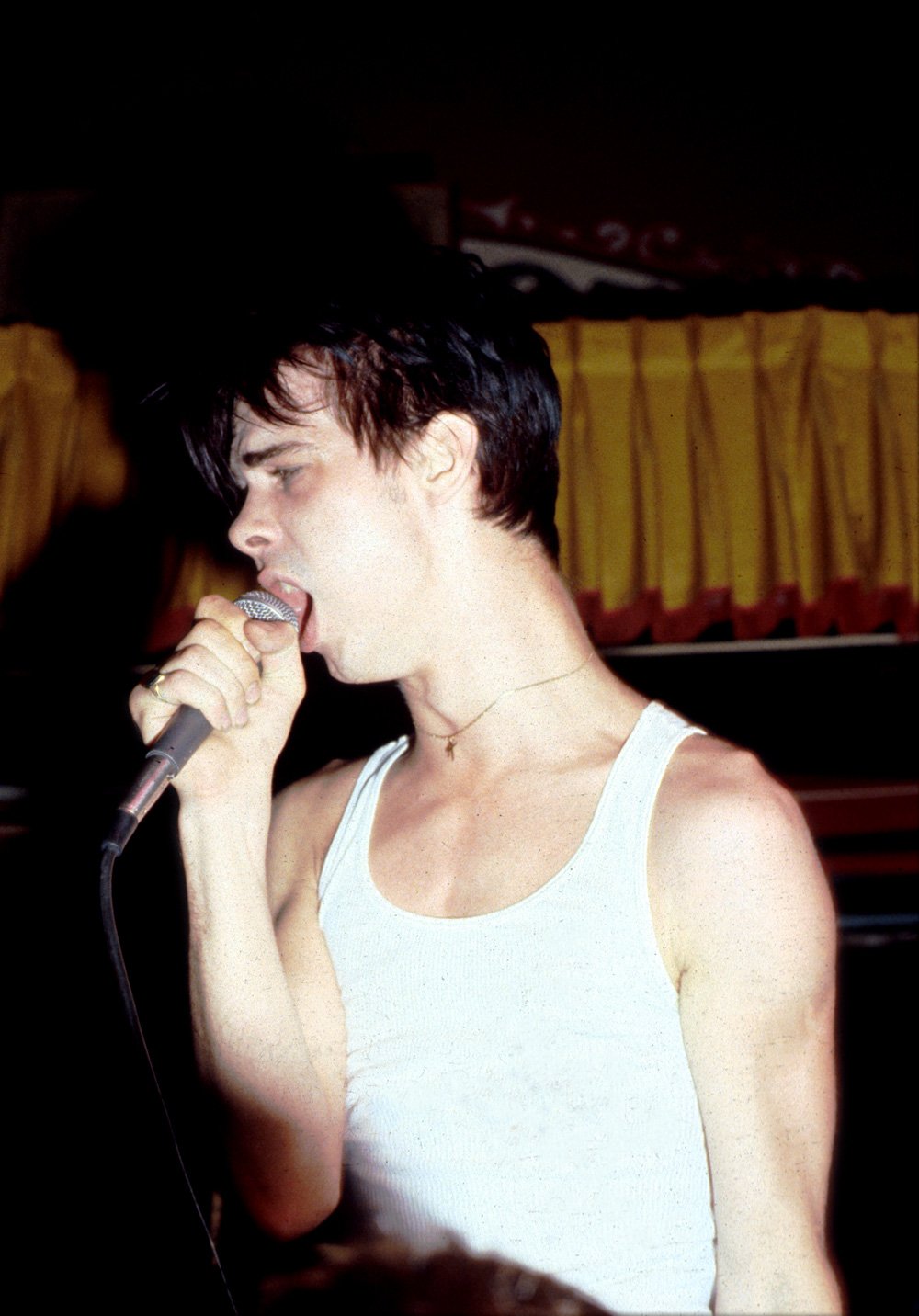

Photo by Getty Images/ Davide Corio / Redferns

Words by Shana Chandra.

No band’s legacy hovers as menacingly over the Aussie music scene, in a more incendiary or frenetic fashion than The Birthday Party, the cult Melbourne-born, post-punk noise band that savaged crowds during its explosive tenure between 1977 and 1983.

A young wiry Nick Cave was the band’s frontman, spewing out surrealist lyrics drenched in existentialism and despair or punctuated with violence and biblical imagery, which were married with the dissonant and distorted chords of the late-great legendary guitarist Roland S. Howard, who was credited with spearheading the band’s sound. Joining them was the deranged cowboy Tracey Pew’s propulsive and rhythmic bass, the raw and primal energy of multi-instrumentalist Mick Harvey and drummer Phil Calvert's experimental sonic palette, culminating in deranged performances that not only nauseated the audience but also ravaged the band members too.

More than forty years later, Ian White has directed the first official doco of the band, bottling its messy chaos and musical ingenuity into gritty, glitchy textures of film alongside never-before-seen footage of band interviews, notebook entries, music videos, and live recordings unearthed from archival boxes, dusty hard drives and forgotten 16mm canisters left loitering in garages. White is the award-winning, UN-commissioned documentary filmmaker who was studying art at RMIT when he first saw The Birthday Party in all their fury, and he takes you on the band’s trajectory from their humble beginnings playing at The Crystal Ballroom in St Kilda, and malnourishment and disillusionment in their London bed-sit, to their infamous tour of the US, their last days in Berlin and their final performance to fans back in their hometown. We sit down with White, to chat about those halcyon days, and how he created a visual time capsule capturing the blaring, pulsating energy of the ‘demented, dystopian boyband.’

Photo by Francine McDougall

Hey Ian, how are you?

I’m well - thanks for your interest in the film!

Of course! It’s amazing – congratulations!

Oh thank you.

I wanted to ask you, I feel like the doco is a culmination not only of your documentary filmmaking but also the music side of your career too, as an art director at Mushroom and Polydor.

I used to see The Birthday Party when I was young, so for me, making the documentary was really revisiting a period of my life. A lot of people, the band included, allowed me access to a lot of old archival material, so I’m opening boxes of people’s stuff, and there’s this smell in the box, you know that smell of old stuff? There were all these textures in there—things that had been lost to us— like aerograms, contact sheets, photocopies and postcards. There were also things like tracing paper overlays on photographs with markup instructions written on them. So a lot of this visual archive I was looking at, really informed the visual palette of the film.

Another thing was that I didn’t want the film to be a nostalgic look back. I wanted to try and capture some of the energy of the time and bottle some of that madness that I remember from seeing the band. A lot of film today has a really generic aesthetic, everything has to look very polished, very slick, and very commercial and I have issues with this because a film can look like anything. If you write a novel, you can write in any number of styles. But when people make a film, it always seems to fall into this very generic aesthetic. I thought, ‘To hell with that’, we’ll just make the film this way; really textured and dirty. I wanted it to have a handmade look.

That really comes through, because intermingled within the scenes you can see these lyrics and journal entries that are all layered throughout it – and so that’s all archival stuff from the band?

Yeah, it’s all [from the] original archive. When I was looking through the old material, there were things like VHS squelch and the leader of Super 8 film. This was all really wonderful to me because we don’t have that anymore and it really reminded me of the time the band was in existence. So, all this went into the way the film was assembled.

Photos by Alison Lea

The film is so beautiful to look at. The animation too is done so well - was it hard to find an animator whose drawings fit the aesthetic of the film?

There are two animation styles, two categories of animation. One is the comic book, graphic novel style, and that comes from a graphic novelist in Berlin called Reinhard Kleist. The band and I were big fans of his, he did a great graphic novel on Johnny Cash, and he did another one on The Birthday Party and The Bad Seeds called Mercy on Me. We contacted him and asked if we could use his drawings as the basis for animation in this comic book style. He was really gracious and said, ‘By all means, go ahead, use what you like.’ I really liked that cartoon style because in some ways I saw The Birthday Party as being some sort of demented, dystopian boyband [laughs]. And so the comic book approach seemed to fit really well with that in my thinking.

The other style of animation, the more fluid, textured style is a guy called Adam [Thomas] of Kingdom of Ludd in Sydney. His work is fantastic and so we came up with the other things, that were more atmospheric like the drug sequences, and we also animated some live concert sequences as well. He used bits from Nick’s notebooks and photos and put those together.

I still can’t get over you opening that box, it would’ve felt like Christmas, just going through it all.

It was a joy. It was also a joy to be given lots of live recordings that had never been heard before and to go through those. And to be given live performance footage. The live footage we found, a lot of it had never been seen before—it had either been lost or forgotten. And that ranged from third-generation VHS dubs to pristine 16 mm film that we scanned. It ran the whole range of quality to beautiful to really fucked up and we used it all. It worked into the visual tapestry of the film.

Photo by Michel Lawrence

Those gritty, glitchy textures you put in there not only reflect the sound of the band, but you’re so right, it also represents that time period. I can’t believe some of this footage has never been seen considering that the band is so cult. And in that way, I’m surprised this is the first time that there’s been a documentary about them.

I believe the band had been previously approached [to do a documentary] but they’d always declined. I was asking Mick about that recently actually and he couldn’t remember who’d approached them. But regarding the footage being lost, the band was surrounded by spectacularly chaotic people [laughs]. There was actually a lot more footage filmed of them back in the day that has never been seen again. There was a concert in Melbourne at the Astor that was recorded on multitrack tape and recorded with three 16 mm cameras, including one in the crowd as well as backstage footage, and which apparently looked stunning. That’s disappeared. Hours of video were shot of them as well, but none of them survived, because people lived very disrupted lives—they moved a lot—so things inevitably went missing. It’s been forty years, so it’s been quite a period of time [since then]. But we did find a lot of other stuff. Someone a few years ago found cans of 16 mm film in their garage and someone found a videotape. Stuff turned up.

What was the process and the time that it took you to collate and create?

The film had its inception during the pandemic. I guess part of the creative intent of the film was to make it using found footage and archival footage, not to go out and shoot a lot, and this may have been informed by the fact that its genesis was during the pandemic when we weren’t sure what was practical to shoot or how much we could shoot. But again, I didn’t want the film to be a look back, I wanted to try and get the feeling of being there at the time, so I was quite happy to make it archival-based.

There were eighteen months to two years of lockdown which we also used to secure financing, which was also more problematic at that time because everyone was unsure about what was going to eventuate. After that, it came together quite quickly, once we had everything lined up. The film was finished six months before it was released but licensing all the music and the material took time. This might sound bizarre, but some of the deals the band had, which they’d had since the early 1980’s were handshake agreements, they didn’t have any paperwork. And they’d always honour those agreements, which is a testament to what kind of people they are - so that all had to be sorted out once the film was completed.

Photo by Rainer Berson Howard

In terms of other people outside of the band that have a bit of airtime in the film, there’s only really Thurston Moore and Lydia Lunch who would’ve seen the band at the time.

I find it odd when you have a lot of third parties—critics, or DJs, or journalists—talking about an artist. With The Birthday Party when the material’s that strong you don’t need somebody telling you that it’s good. The band are also very articulate, and they’ve never really opened up that much about that period of their lives, so I found it really interesting for them to talk about something they very rarely talk about. None of them are very nostalgic or sentimental people. They’re all really creatively engaged and busy with what they’re doing in the here and now. So, it’s not usual for them to spend time reminiscing, and I wanted to take advantage of that.

Some of the footage of Nick, Mick, and of course Rowland talking seems to be older.

Yeah, so part of the genesis of this film goes back to the early to mid-2000s. Rowland S. Howard and his producer Lindsay Gravina had the idea to make a film, and they’d started collecting and doing interviews. But Roland fell ill and subsequently passed away, so that project was put on hold and the material just sat on a hard drive in a drawer for fifteen or more years until it was picked up for this project. So that was really invaluable, in that we had around three hours of interview footage with Rowland. When we do see the band talking, we use the interviews from that period.

Photo by Getty Images/ Davide Corio / Redferns

The band has such a cult following that even when I lived in Melbourne ten years ago, you could feel the band’s presence hovering over the music scene there. It’s such an important band to so many and I was wondering whether it was hard for you to choose what was included in the film?

That was quite instinctive. I will say one thing—you see a lot of band documentaries these days which are clearly heavily curated by the band or their management. This couldn’t have been further from the case. I don’t think I was ever told, ‘You can’t say that’ or ‘You can’t go there’ or ‘You can’t put that in.’ The band was really understanding and respectful of the creative process and chipped in when they thought something could go in [at a particular point]. But I was never given directives from the band.

Very early on we established this creative direction that the film would be archival-based and be told in the band’s words, we weren’t going to analyse the band or have other people talking about their vision of it, and it all came together quite quickly - it was just smooth, and fluid and it just flowed. In the film, the band says that they never had a band meeting or discussed their creative direction and the film was the same really. It was all done very intuitively

Do you think they trusted you and wanted you to do direct because you had been there originally? Was that a big thing for them?

I don’t know whether it was a big thing or just that we had a lot of common references. They’re a little older than me, but essentially we come from the same place and the same era, so there are a lot of common reference points and ideals from that time. I can’t speak for all of the band but for a number of them, I’d say the ideals of that time are still with them, and probably with myself too.

Photo by Alison Lea

One of my favourite parts of the film is you showing the full video of ‘Nick the Stripper’, and the band talking about how they went about filming it – setting a chemical filled pond alight in a rubbish dump, bussing people in from a local psychiatric hospital…

It’s out of control. That band was a trip. They really were. They were unique and unlike almost any other band. You can see bands that are louder, or harder, but you’ll rarely find a band that has that kind of creative intensity. There was something alchemical about that band. It was remarkable.

I also found it so interesting that so many people described that being at one of their gigs was like being ‘annihilated’. That word came up again and again and I think that’s such an incredible feeling to be able to transmit to an audience.

Their shows were phenomenal. Many people have come up to me and spoken about their experience of seeing the band since the film’s release. People have said they’ve never been to shows where they’ve felt physically afraid, or physically sick, or they felt terrified or nauseated from the sound. They felt this palpable sense of fear in the room when the band was playing, or even before the band went on. Mick Harvey says that before he’d go on stage, he couldn’t speak to anyone for thirty minutes. They really channelled something. At best their performances were almost transcendent.

Photo by Peter Milne Howard

Did the tempo of the music dictate how the film was cut?

Absolutely. Another thing that’s interesting about that film is that we were working off really good, multitrack live recordings. Some of the live footage was 16 mm recorded without sound, so we were striping sound from multitrack live tapes onto the 16mm film, marrying up visions and recordings.

After you finished the film, or during the process of creating it, did it change your perspective on the band in any way?

It brought back to me how good they were and what phenomenal musicians they were. It’s really easy to look at the chaos, , the performances are clearly intense and chaotic, but if you look beyond that, the band never loses track of where they are, they’re super tight, and they’re often juggling really complex time signatures. Phil Calvert the drummer said to me once, that no matter what was going on, how crazy it was, they always knew exactly where they were at any point in a song. That really came home to me when I was working with the footage, just what a phenomenal band they were musically, which is often overlooked with all the mayhem.

The other thing I guess was that a lot of music from that time has really dated, but The Birthday Party’s music hasn’t dated at all. It really sounds as fresh now as it did forty years ago and that’s a testament to how timeless they are as a band.

Mutiny in Heaven: The Birthday Party is currently in theatrical release throughout Australia, is available on Prime Video in the US, and is now screening in UK theatres.

Photo by Getty Images/ Davide Corio / Redferns