Chris Middlebrook: Documenting Three And A Half Decades Of Australian Skateboarding

GIF and imagery provided by Chris Middlebrook.

For the last few years, every time I’ve asked Chris Middlebrook what he’s been up to, he’s always answered with something along the lines of: things you’d be hyped on.

He’d continue telling me about filming music videos for his good friends, Eddy Current Suppression Ring, his latest finds, whether it be an old t-shirt or a tape he’d just logged with some forgotten gems, and of course, the ongoing progress of his book, Pause. No matter what it was, he was right; as a fellow nerd, I was always hyped.

The progress of Pause was what always intrigued me the most. A three-year-long process of sorting through his three-and-a-half-decade-long archive of hard drives full of HD footage, hundreds of tapes, polaroids, 35mm and X-Pan negatives, and thousands of feet of Super 8 reels to compile a visual picture of his life documenting skateboarding. And with a resume that includes filming Lewis Marnell, working alongside Greg Hunt and Benny Maglinao on Alien Workshop’s Mindfield, a decade of work with Nike SB Australia, and co-founding April Skateboards with Shane O’Neill, it’s hard not to be impressed. Pause brings all this and more into its three hundred and fifteen pages, while also giving a glimpse into Australian skateboarding history.

To coincide with the release of the book and exhibition at Hillvale Gallery in Melbourne, I sat down with Chris to talk in depth about the making of Pause. Also, for those in Sydney, Chris is doing a pop-up at Pass~Port Store and Gallery on Thursday, the 15th of January, and if you’d like to buy a copy of Pause, you can do so here.

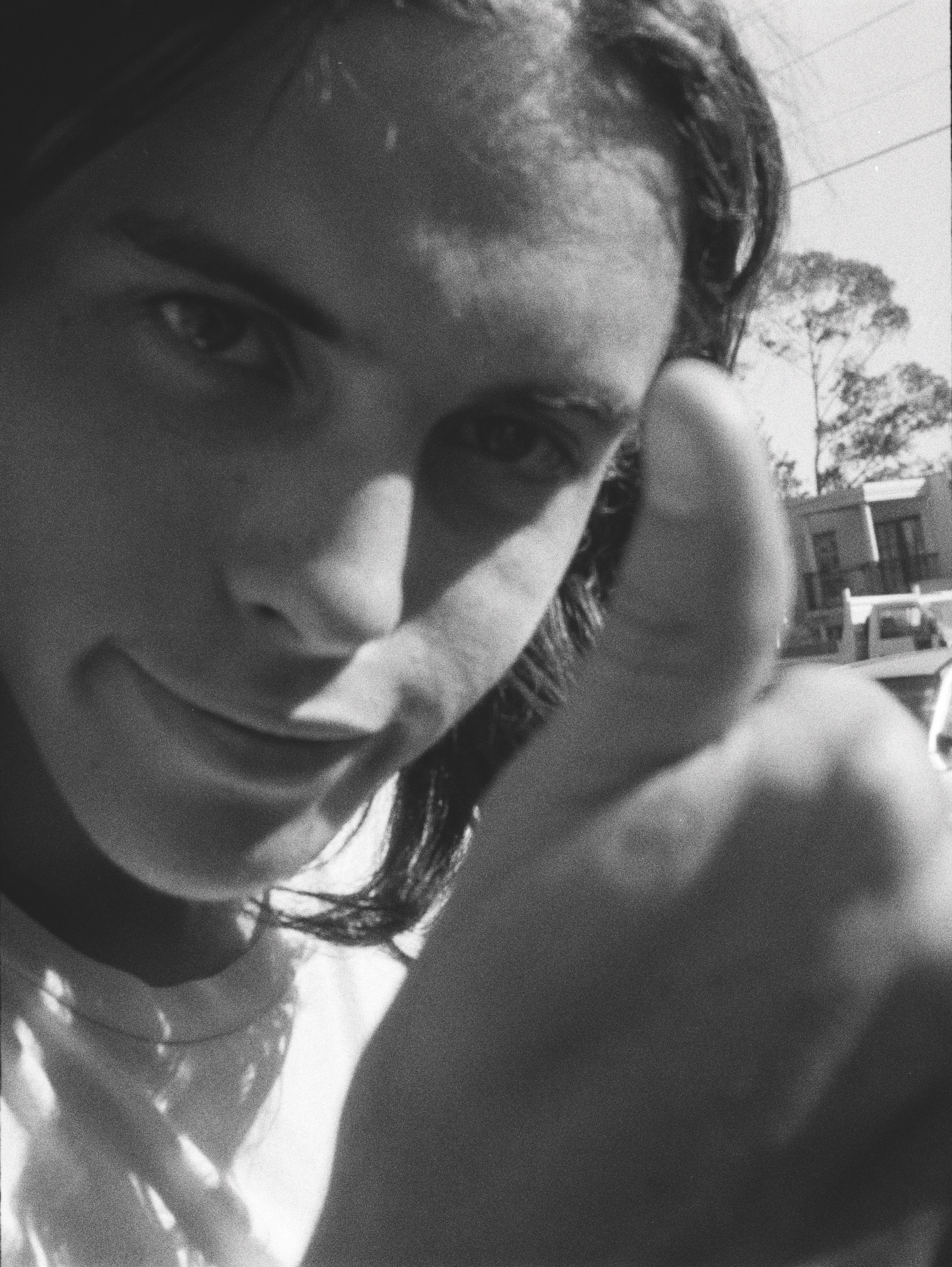

Jason Dill in Melbourne, 2008.

When we spoke in the early days of the project, you originally had other ideas for it. What were the origins of the book?

The original idea of figuring out how to archive video footage started in 2013. HD had started, and VX was pretty much done. I’d hurt my neck, was stuck at home, and I was trying to think of something to do to keep myself busy. Fifteen-second Instagram videos had just started, so I was also looking at archives for older clips. At that time, I was thinking of doing a double DVD, one of PAL and another of NTSC footage. I pretty quickly realised going through eight hundred tapes was going to take forever, so that idea quickly vanished.

Five or six years later, I thought I’d do a few different books and zines, one would be 35mm photos, one polaroids, one X-Pan’s. I wanted them to be all different mediums so they could be different sizes, and it would keep things consistent. As I started to go through things, I realised there would be too many different projects, and it might not be the best option. In 2022, things really started to come together after a trip to Sydney, where Jack O’Grady turned pro, and I had lots of 35mm photos from the trip. I was looking through all the photos, and there were some really cool X-Pan shots I liked, but I realised they were never going to go anywhere. The Skateboarders Journal wasn’t around anymore, skate mags didn’t really exist, and I didn’t want to put them straight on Instagram. I was like, maybe I’ll start looking at making a zine. I had a bunch of photos; most hadn't ever been seen, not even by the people in them.

I decided to mock up this little A5 zine, which had some Hi-8 and VX screengrabs, polaroids, some Super 8 strips and things I had always thought would be in a book if I ever made one. I showed it to Sean Holland [Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief at The Skateboarders Journal], and he was like ‘Nup, Midds, you can’t do this, if you're gonna do something it’s got to be big.’ I knew he was right, and the mess I was about to get into was going to be huge. I spoke to Mike O’Meally, too, as I knew he was in the same boat with a big archive.

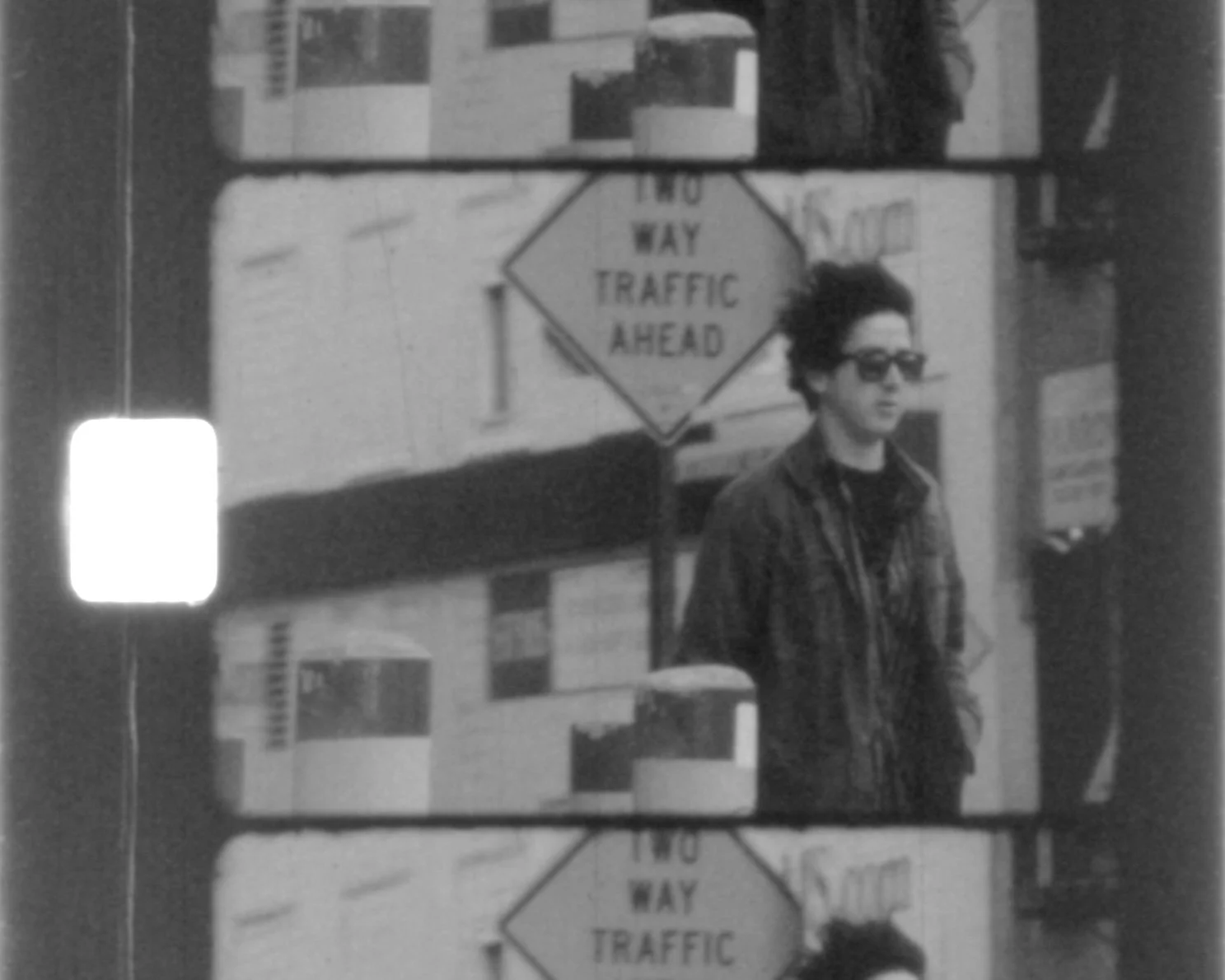

Dylan Rieder in Melbourne, 2008.

He’d have so much, especially shooting film for so long.

Yeah, he sent me some photos of all these cartons of negatives he has. He was like, ‘What are you waiting for? Get into it.’ I kept putting it off because I didn’t really know how to do it. I didn’t know how to use InDesign, make a book, fund it or even publish it. I also didn’t know how to screenshot video grabs properly or how they would look. I was a few months into getting video grabs together, and World Artefact Society came out, which was full of that kind of stuff. I spoke to Al Boglio and Aaron Meza, who worked on that production, to get a better understanding of it. That was super helpful, but still, the whole time, in the back of my mind, I’m thinking: Is this going to work? Will these look okay once they print?

For sure.

Then I started going through everything, logging all my tapes, screenshooting everything, going through HD stuff and exporting entire sequences of a clip or a video to put in the book. It was hours of work. Then, once I got to the Super 8, I was scanning frame by frame for thousands of feet of film.

Hillvale Photo helped a lot with the book and its launch. How did they get involved?

I was at a wine bar with Beci Orpin one day, and met Sarah Pannell, who is a part of the team at Hillvale. We got chatting, I told her about the book, and she told me to hit her up if I needed any help. I didn’t think much of it, but I saw her about a year later, towards the end of 2024, and she asked about the book. I told her I had a lot of material ready, I was just struggling to lay it out and how to do it. She told me to come past to Hillvale, so I went in and met with her, Jason Hamilton and Andy Johnson. They were stoked on the whole project and agreed to come on board and help out with book editing, designing and also agreed to host the launch and the exhibition. There is no way it could’ve done it without them.

How much did you find while going through the archive that you didn’t remember having or had never seen before?

In the book, I’d say fifteen per cent of it is things in there I’d not seen until I went back through the archives. Maybe I’d seen them, but was seeing them differently now. With tapes, you would just capture the slam, the trick or the random thing that happens. Now I’ve logged the entire tape for some of them, I’d sit there and watch the whole hour, looking for something that I hadn’t noticed before. There are Super 8 frames of Joe Castrucci in the book I didn’t know I had; they were at the start of the reel, so they never got transferred. It was just him pushing with a camera; it’s nothing special, but I had never seen it until I put it into the scanner.

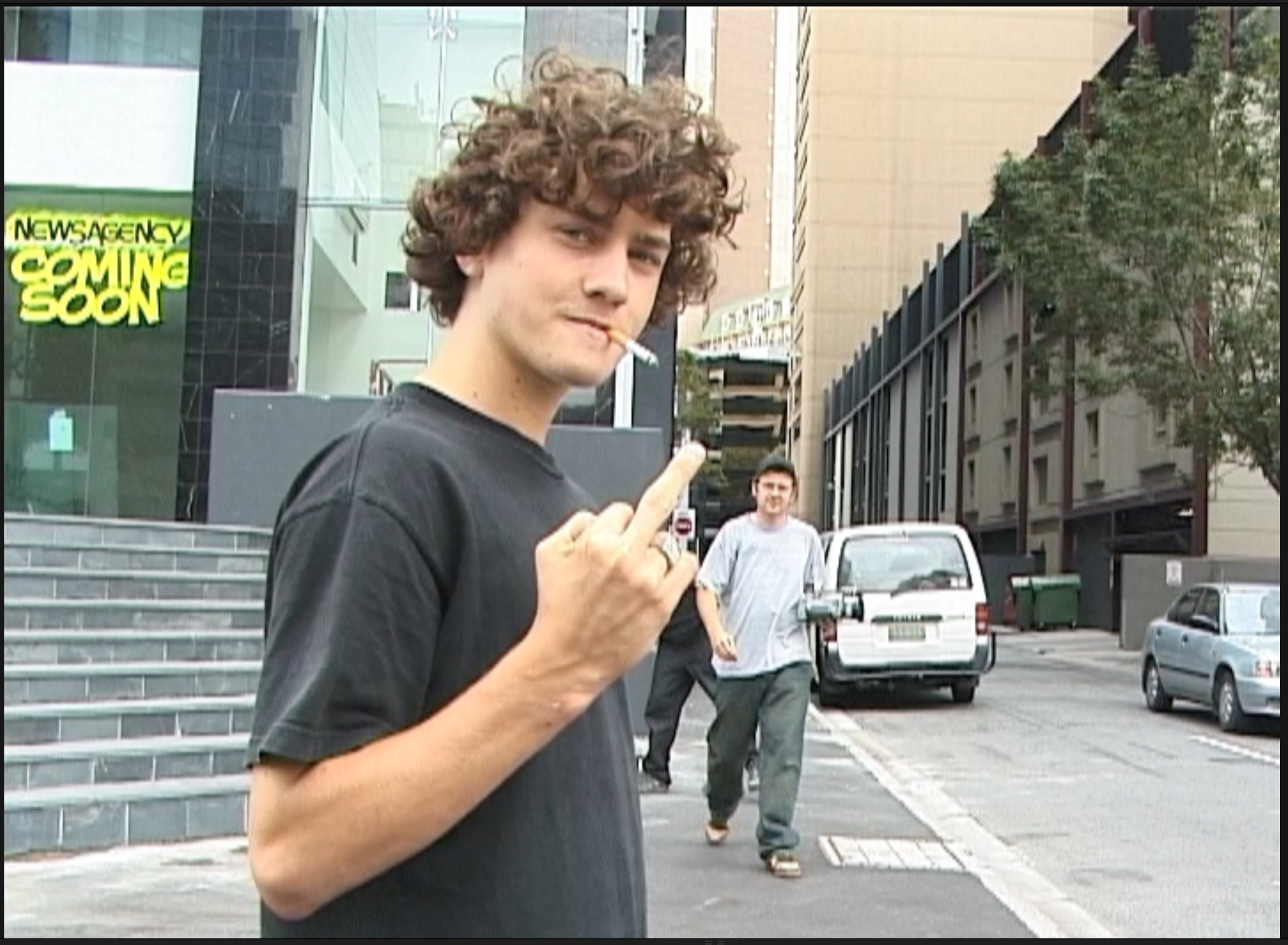

Dustin Dollin in NYC, 2006.

That’s so cool, especially being from the Mindfield era, which is so important to your story and also to skateboarding.

It was surprising, I didn’t realise what it was until I checked properly. The next bit is him filming Stefan [Janoski]. There are just bits like that you notice more when you capture it and pause it. Some things look so different as a still image.

How was seeing some of these things as a still for the first time?

It was super impressive. When you see the Super 8 as a strip, then as a single image, it can have a different vibe. Same with finding one single frame out of a video.

Totally. The triangle looks so good as a still on the cover.

Yeah, it was always going to be the cover. It’s always been my favourite thing I’ve filmed. Ever since I got that film processed.

I was shocked when you told me it was just this tiny thing behind some random shed in the country.

Yeah, it looks like it’s signalling aliens to land or an art installation. I remember seeing it straight away and being like ‘What is that?’ There are all these different angles of it, that’s just the best one, but it’s only five seconds long, so all the footage you see of it is looped. There are three angles in colour and three in black and white. No one’s allowed to see those [laughs]. I’m stoked because it was such a cool thing, Greg [Hunt] liked it, and it ends up in Jake’s [Johnson] part.

And it’s placed at one of the most iconic times in the video, just after he lands the fakie heel down the nine at the Brooklyn Banks.

Anything I had in that video meant a lot, especially to film Super 8 stuff and to bring that all back and to have the spinning pyramid to be the cover of the book.

Keith Hufnagel, Plaza, Melbourne, 1995.

It’s cool to me because in Mindfield, the two Super 8 shots that stood out the most in that video were that and the globe-looking thing, and you filmed both of those. Where does the book start in pictures?

It’s all pretty much in chronological order, obviously, things jump in certain zones, because projects and years overlap, but it’s pretty consistent. It starts in 1990, even though there are some photos before that, that’s when I started consistently using cameras. At the start, it’s still photos, then it gets into video with Hi-8 from the early 90s to late 90s, then Super 8 and VX when we get to the Blank Vandals era, and then that continues to Lewis [Marnell] and Dustin [Dollin], then into Nike, Mindfield and onto HD then all the different skaters I worked with all the way through to now.

How did you split up the photos in the book so it wasn’t too overpowering with the same people?

It took me quite a while to get over the fact that I was putting together a project that tells the story about my life documenting skating. That was the hardest part. It felt quite self-indulgent for a long time. Once I got past that, it fell into place a lot easier. I started writing the text that tells that narrative for the back of the book, and it made sense that the imagery would follow that. People come and go through the book in line with who I was skating with and what the projects were at the time. It’s also what I thought was nostalgic to me and what would be of significant interest to anyone else. It’s not just the superstars of skateboarding; there are a lot of pro skateboarders in there for sure, but there are also a lot of Melbourne and Australian skaters and people who were relevant to the city or the time.

Tommy Guerrero, Prahran, 1990.

Even more than that, too, it’s people from your life. When we were talking the other day, you were saying how you wanted to put in your mates from Frankston that you grew up with, because they were a big part of your life.

Yeah, the early '90s section is all the guys I was skating with and learning how to film with are important. There’s a page of the Sail Yards too, with everyone from there and all the different crews. It was all about the journey and who I was around.

Yeah, what I found most interesting when you walked me through the book earlier in the year was that yes, it is your story, but it also felt like this story of skateboarding in Melbourne on a global level. All those images of Dylan Rieder, Jason Dill, and Omar Salazar in the city. It feels like the telling of this part of Australian skate history that’s been untold. Even growing up, I’d always hear rumours of Dill doing stints here and people seeing him on Brunswick Street getting a coffee.

The connections were different back then; it was a different set-up. I don’t really know why. Maybe skate trips were set up differently, maybe the scene was a little tighter, maybe there were fewer filmers and skaters, or maybe because there was no social media, people felt like they could do what they wanted. But yeah, there used to be tours every summer, and that crew would always roll together. If they were in Sydney, they’d be with [Su Young] Choi; if they were here, they’d be with me, and O’Meally or Andrew Peters would always be on the trip. If people were going to come all this way to Australia, they were going to stay and hang out a while. The lack of social media is a thing, too. Even you bringing up people talking about seeing Dill at a cafe, things were more mysterious back then. Less cameras, less socials.

Yeah, totally.

It was a different era.

Lewis Marnell, Kings Way, 2004.

How did Pause come up as the title?

One of the first things I did when I started taking photos was pause skate videos and take photos of the TV screen in the dark. That’s what the photo of Matt Hensley is, and there’s one of Guy Mariano, too. I remember being stoked on those photos as a young teenager. The Hensley one was the original Pause; the book is made up of film stills and paused video frames, so when the Pause came to mind, I thought, ‘Why didn’t I think of that sooner?!’

What’s your favourite image in the book?

The X Pan photo of Rowan Davis in Auckland, ollieing from parking sign to parking sign. Geoff and Bryce are in there getting their shots, Raph Langslow is the top corner, snapping a photo on some little digi cam. I just snapped off one frame before I started filming, and that's how it came out.

I also have a particular attachment to the photo of Tony Hawk at the Olympics; that whole experience was pretty surreal.

Rowan Davis in Auckland, 2024.

I know you’ll never think about it like this, but what was it like going from skating the prefab Frankston skatepark and then being at the Olympics?

It was a cool experience. I remember hearing Tony had been skating the park the day before, and I wished I’d been there. Then, sure enough, the next day we were there early for practice, and he turned up. I remember taking that photo and being like, ‘Damn, if that photo comes out, I'll be stoked.’ It was an empty stadium, a total ghost town. It was a million degrees, he’s dripping sweat, and he’s doing his thing. The thing he’s been doing his whole life. I’d been to contests but never really been around anything on the scale before. That week or so I was at the Olympics, I was just shooting everything, it was crazy, and I knew it was never going to happen again.

Something that I wanted to mention was when we were in the gallery the other day, and your friend from Frankston came in and was telling his son that you always had a camera with you. It’s so nice that this project is bringing people from every era of your life together.

I’m only starting to realise what I’ve done, and that’s not some dumb like ‘I never realised’, but I didn’t realise what I was creating until I’d packaged it together and started to see people's responses and appreciation for it. It’s been quite humbling. Even people outside of skateboarding seeing it, it’s been nice to hear them be like, ‘Wow, you’ve spent your whole life doing this.’

Tony Hawk, Olympics, Tokyo, 2021.

It's rare to have something that you spend your entire life documenting.

Yeah, it’s surreal. I’m stoked I did it, and I still get to. It’s interesting to be this age and give back to the community. Even though a lot of what I’ve done is videos, it’s more of a summary of what I’ve done and who I worked with instead of being about the videos themselves. A lot of the other projects have been for other people and for brands, which has been great, that’s what I wanted to do, but it’s kind of nice that the book is all images I’ve made together in one place.

Chris Middlebrook, Brunswick, 2026.

And also, even though that work was something that you were super proud of and put so much time into, it was still work, it was your job.

Well, for a lot of the time, it wasn’t even a job; it was for passion before it became my job.

I got an immense sense of joy out of seeing others achieve what they wanted to do, whether it was the trick or even someone getting sponsored or finishing a video part from what we made.

I know a bunch of people were involved with the book. Do you have anyone you’d like to thank?

Oh man, so many people. Everyone I’ve ever skated, filmed or shot with, but specifically – Raph Rashid, Beci Orpin, Sean Holland, Mike O’Meally, Jason Hamilton, Andy Johnson, Ellen Spooner, Max Olijnyk, Bryce Golder, Shane O’Neill, Geoff Campbell, Brett Margaritis, Ben McLachlan, Kerry Fisher, Steve Gourlay, Danny Young, Brendan Huntley, Brad Barry, Mikey Young, Raven Mahon & Jess Ribeiro.

I feel very fortunate to have enough time and space to go through the archives and compile them into a book. I'm grateful for the opportunities I’ve had and the contributions I’ve been able to make to skateboarding. I hope people enjoy Pause and find some inspiration in it.