Radiohead: The Album Covers

The images that grace the covers are etched into the consciousness of fans the world over, but the stories behind them remain largely untold.

Radiohead have released nine studio albums, and since The Bends in 1995, Stanley Donwood has been responsible for the covers and accompanying artwork for every one.

His role has evolved into less hired gun, and more of an intrinsic part of who the band are and what they stand for. One blustery evening in Bath, after a couple of glasses of vino, we were lucky enough to sit down with our guest editor in his studio as he pulled out the records one at a time and went through the laughs, tears, self-hatred and last minute jubilation behind each one.

More than simply designing one image for the cover of the CD case or the record, Stanley’s produced a whole catalogue of work for each release that’s as sweeping and complex as the records themselves.

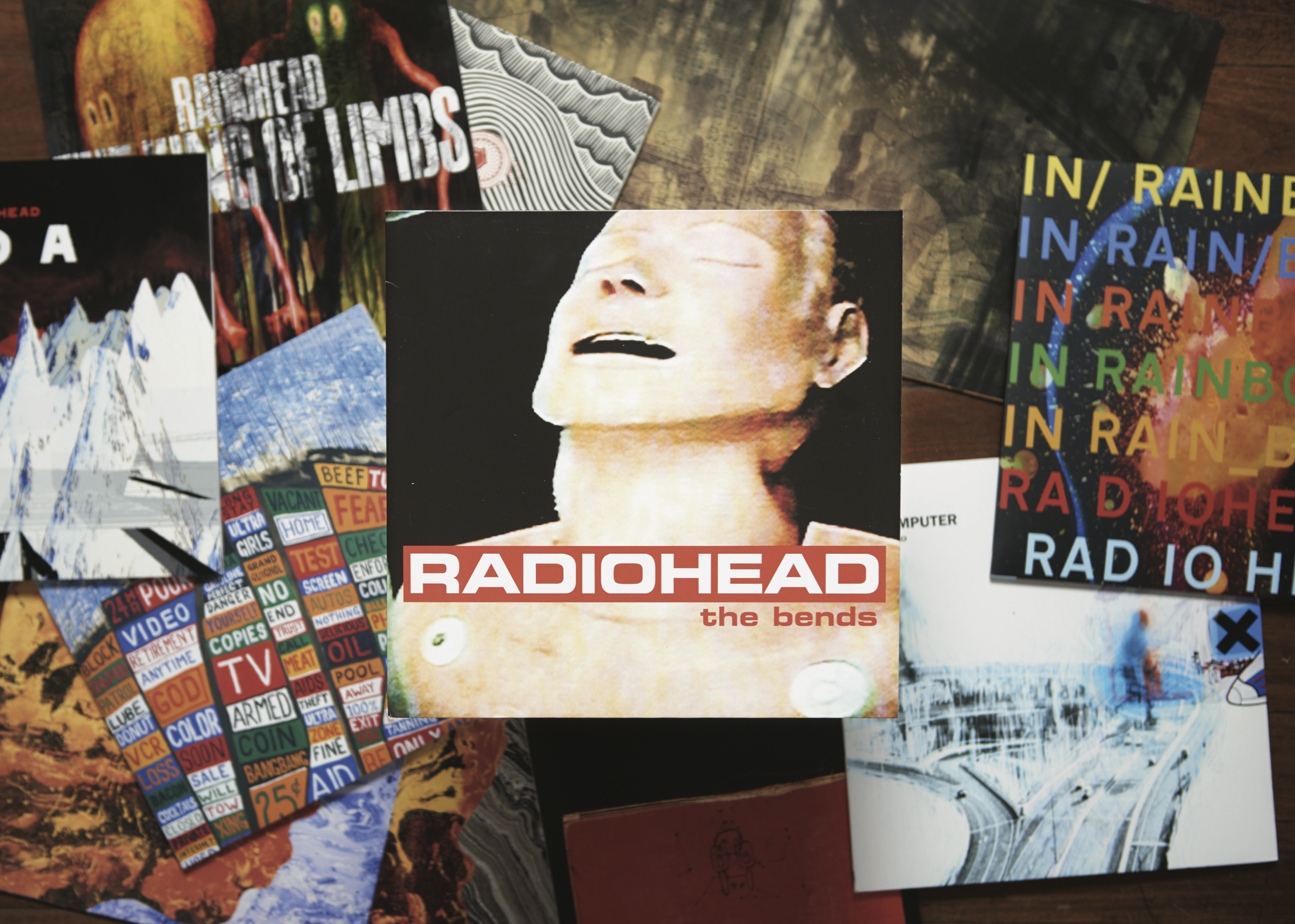

THE BENDS

The first record I did was the first single from The Bends—“My Iron Lung”—and I’d never done a record sleeve before. I was living in this share house down in Plymouth where we had this payphone on the wall that we had the key for. So youhad to pay for calls, but when we ran out of money we’d unlock it and get the money out. The phone rang and it was Thom, “Do you want to have a go at doing the record sleeve?” We went to the same university (Exeter) where we both did fine art and English literature, but we used to sneak into the lovely lush carpeted graphic design area from the shitty hell hole of the fine art building. We’d both fucked around on computers a bit and we taught ourselves Photoshop really badly—I still don’t know what half of the things are, I think I’ve found a very narrow skill set that I refuse to deviate from in case I fuck everything up. When you first get Photoshop it’s like, “Oh my god, bevelled edges, embossed, chrome effect, wow!” And you fucking do everything and pile everything into one picture. Somewhere in here I’ve got loads of A4 printouts of veraciously poor record designs. It’s a very dangerous tool in the wrong hands, Photoshop, like a nuclear weapon. I’ve got a feeling that I didn’t particularly like their first record, Pablo Honey. I was into dance music before I got into the other things that went along with dance music. And they (Radiohead) used guitars. “Guitars? Who uses guitars?” So I didn’t really like it. But then I was listening to it and there was one on The Bends that I particularly liked called “Just”.

This is the amazing thing, Radiohead record covers—a little known fact, published in Monster Children for the very first time—are always last minute, always last minute. Apart from The Bends, which was, now, comparatively minimal at the time, but for me it was like, “Whoa!” But the cover, we had a deadline, and we were like, “Fucken hell, what are we going to do?” We didn’t have a cover, we had a few possibles, but we were young then, like 25 or something. The Bends was interesting because somehow we managed to sneak a video recorder into a hospital—that’s not right is it? You shouldn’t do that. But I didn’t think about it, I was young. We’d heard that there was an iron lung in the hospital, and I wanted to film it because of “My Iron Lung” the song. We eventually found the iron lung and it was rubbish—it’s just a grey metal box. Nothing to it. So we’re wandering around, and I was trying not to film the old and dying people, and then I was in a room where they have the mannequins they use to teach people how to bring someone back from the dead. The cover of The Bends was a dummy that had metal nipples that were in slightly the wrong place so that you can put the paddles on to go “zzzzt”. I vaguely remember me and Thom arguing about how big “Radiohead” should be on the cover. I was like, “Fucking massive mate.” And I wanted “The Bends” to be central. And he was like, “I want it over there,” so I conceded and he won. We have many arguments, but they’re very genteel arguments about fonts and composition, we don’t fight, fight.

OK COMPUTER

It was really with OK Computer that I got more heavily involved with the band. Because I could ride my bike to where they were recording—it’s only about an hour from Bath on a bike—and they had this beautiful house in this place called St. Catherine’s Valley. Time’s stuck in about 1940 up there. This lane starts off ok and then it gets more and more filled up with potholes, until you get to this big old Elizabethan manor house with its own church nestled in this tiny little cocoon-like valley. So yeah, they rented it and moved all their gear there and recorded the album there. They had one of those TV shows recently, Countdown to the Best Record in the Universe Ever, and it was getting near number one and OK Computer wasn’t on it, and I thought, “That’s weird,” but then it turned out that it was number one. They’d had all these people for all the other records, like the producer talking about it and then the band talking about it, but they couldn’t get anyone to talk about OK Computer apart from two of the cleaning ladies who used to come and clean the manor house. (In a thick West Country accent) “Oh they were in there and they were making a hell of a racket...” It was brilliant.

I was working as an unpaid artist in residence in an internet café out the back of a pub, but I didn’t have a computer of my own, so mostly when they were making OK Computer I was making the website because I don’t think that Parlophone (Radiohead’s record label at the time) thought that there was much future in this internet thing. The artwork for OK Computer was done in various places, but also at Thom’s house in Oxford. He used to live in this little semi-detached suburban house with a view of some trees that was very nice. But I was in a bit of a dark place with making that artwork, I kept seeing the trees and imagining a post-nuclear scene and what it would look like after a nuclear explosion—sticks and white ash everywhere. The view was a bit too lush. When OK Computer came out the record company heard it and they were like, “Shit, any fucking chance of making any money off this band is... no way.” They really didn’t like it. And then the reviews came through when the band was playing in a little nightclub in Barcelona—because they weren’t a big band then really— and the reviews were fucking extraordinary, people really loved it. As a result I did a little show called No Data to promote the record, and I think I stuck these prints from the making of the OK Computer artwork up with double sided tape and they were all for sale for the cost of a giro, what you used to get for a fortnight on the dole, which for me was really not long ago then.

KID A

Where did we do Kid A? We went to this crazy manor house somewhere in the Cotswolds, and I’m not entirely sure, but I think that it was owned by some upper class English family that were a bit pally with Hitler. The band had the ground floor, and then the higher up in this house you went the more derelict it got, until there were these bizarre rooms, empty apart from a sink on the wall, a single chair, a man’s chair piled up with 1950s newspapers, and then so many dead flies on the windowsills that it was thick with dead insects. Also, I went for a walk—beautiful Cotswolds you see, lovely, lovely, lovely. But not really, because there’s all these fields with these big wooden crosses, and dangling from the arms of the crosses are all these decaying birds strung up by their necks, just flapping in the wind.

They’re weird, country people, I don’t know what they’re about really. So that fed into the Kid A artwork. I think I painted a few of these strange structures. After doing OK Computer I got fed up because you’re just sort of doing this (mimes looking at something and drawing) and I had this idea that your body holds loads of memories all over, so I wanted to do big gestural stuff. So Thom rented a place in an old warehouse in Bath afterwards, and we got a load of massive canvases and a load of paint brought in. And I hadn’t painted since I was doing A-level art or something. Me and Thom were up all night making loads of covers for Kid A. But it wasn’t called Kid A. They all said “Radiohead” on them, but they all had different titles. I don’t know, 20, 30, 40 different covers with titles. And we sellotaped them all up on the wall in the kitchen and the studio, so in the morning when the band came in we just said, “Can you just go to the kitchen because, fuck, we’ve had enough.” And that’s how we ended up with Kid A. Typeface, artwork, title, everything. Like I say, it was a last minute thing.

AMNESIAC

I wanted Amnesiac to be like something that had been forgotten and then rediscovered. Like when you find something really curious in an old piece of furniture in a junk shop or an attic. We went to lots of second hand book shops and bought old hardback books—we were scanning all the blank pages from the front and the back of the old books, and I had a big folder on my computer called “Old Paper” that was full of yellowed, dog-eared, and coffee-stained pages. I’d been spending lots of time wandering the streets of London and had gotten really obsessed with mazes and the etchings of Piranesi, and also the legend of the Minotaur. I’d done some big black and white paintings that were supposed to be the walls of the labyrinth where the minotaur was imprisoned, so they were marked with “m”s and “minos” and scratches, and I had lots of photographs from various cities and sort of collaged them together with lots of drawings. We (Stanley and Thom) were both doing lots of drawing and then super imposing them on this old scuffed paper. This was definitely the CD days, and I think there was a double ten inch record too. I really wanted to make this book for the special edition; a tattered, old, broken-spined, red book that was the front of the album. So I made a sort of withdrawn library book—the sort of thing that you would find in second hand book shops—and it had a little ticket in the front of it where they used to put the stamp that told you when you had to bring it back. Then I got everyone’s birthdays—all the crew and everyone’s family’s birthdays—and I bought one of those little stampers with the numbers on and put all the birthdays in.

Oh yeah, and I bought one of those really shit little printing kits with the little rubber letters that you put on with a pair of tweezers, like a kids’ thing. So I used that to do all the lettering for all the singles and stuff, the “John Bull Printing Kit” or something it was called. So we made the book which was really nice, and then the weird thing was that we ended up going to Los Angeles because it got nominated for a Grammy for Best Recording Package. So it’d come from all of this wandering around London, and y’know, writing down people’s graffiti tags and photographing litter, and the strange trajectory of something that was very incongruous really, was finding myself in the city of Los Angeles. I think it was the first time that I’d ever been there. It was kind of horrifying really, in a lot of ways, particularly with the not being able to drive thing. So we went to the Grammy award thing, which was really weird. I’d never, ever been to anything like it before—it’s not something that I make a habit of. But everyone’s really dolled up, there’s red carpet—swish swish swish—everyone’s got makeup and perfume on... You know in the library sometimes tramps come in and just sit there because it’s warm? I felt like one of those guys. Just totally out of place.

So anyway, we win this Grammy and me and Thom go up onto the stage with no idea what to do. He’s done this before, but I don’t know what to expect. So there’s a fucking autocue, and there’s all these people, and you’re looking at the autocue, and all I said was, “Err,” and then Thom said, “Err”, and all we said was “err” a few times. And then the autocue said, “Wrap up now,” so we just read what was on the thing and said, “Wrap up now,” and that was it. Then we got our Grammy and went through into the backstage of the thing, and we took a wrong turn somewhere in the bowels of this place—I think it was the Staples something, and Staples is like a fucking stationary shop, and they were sponsoring this massive fucking place. This was 2002, and the Americans were well jumpy about the twin towers thing—all of the homeland security people were on it and really paranoid, hair- trigger sort of thing. So there’s two little scruffy English guys wandering around the back of this thing, and the security come up with their guns and everything, and they’re like, “Excuse me sir, what are you doing, do you have clearance?” all that sort of thing. And we’re like, “Err, we just, err, we just came from the err, stage, we just got a Grammy...” “That’s of no concern to me sir, will you step into this room...” I was like, “I’m not going into a room with you and your gun.” We were just thinking, what the fuck are we going to do? We’re in the bowels of this massive building, in the city of Los Angeles, there’s people pointing guns at us, we’ve just won a Grammy, it was like, we’re going to be deported or something (laughs).

So eventually, after lots of argy-bargy, someone from the Grammys came down and smoothed things out and led us away up to the bar where the band’s management were. We were white as sheets, “Large vodka and tonic please, make that two.” It was a very strange introduction to America for me. So that was the trajectory of the Amnesiac artwork, from wandering around rainy London with no particular idea of what I was going to do, to having a gun pointed at me in a sports centre of some kind in LA. This sort of thing seems to happen to me all the time, I don’t know why.

I MIGHT BE WRONG: LIVE RECORDINGS

I saw them play last May, hearing them play “Burn the Witch” and all that live. And I remember thinking before that, “How the fuck are they going to do that live?” But it was like, “Wow.” They were on such good form, man, it was amazing. I’ve got an idea for the next one—for the live version of that (points at A Moon Shaped Pool) I’ve got to learn how to do something. Do the artwork, anyway. I need my other daughter back, however, because she has the information that I require. She’s done a lot of work with what I want to do, and it involves lots of chemicals and mixing them together. it’s not dangerous or anything. I Might Be Wrong, the live album, oh, it’s got an inside sleeve - I like this one. It’s fireworks. But we joined them up. I think that Thom took the photos of the fireworks and we joined them up. I got into trouble for this one because I used part of the London A-Z map. This was when I was doing these weird Piranesi-inspired wanderings around London, but that’s the bit that I was particularly interested in. This was still with Parlophone I believe.

HAIL TO THE THIEF

The band had said that we were going to go to the city of Los Angeles in the state of California in the country of the United States of America, and the idea was to make a record in two weeks. We’d been spending quite a long time making records up until this point, on average about two years of pain and suffering. So this was, “We’re going to go punk and ‘fuck it!’ like the Sex Pistols. Really fast, two weeks.” And I thought, “Radiohead,

punk, make a recording in two weeks, what shall I do? I know, I’ll join the National Trust,” which is a large paramilitary organisation in the United Kingdom. Well, it’s not really paramilitary, but it’s actually got more members than any of the political parties in Britain, and it’s devoted to old houses, posh gardens, and tea rooms as far as I could te.. There’s National Trust properties all over England, but the problem was that I cannot drive, so I had to go to all of the ones that I could get to on my bike, and on public transport from my house.

At the time, I was very interested in what happens if you take photographs of the land and then photographs of the sky and then rotate the sky 90 degrees. Clouds are normally horizontal, but if you rotate them 90 degrees then obviously they become vertical. And you would not believe how vulvar clouds look if you rotate them by 90 degrees. They look like massive cunts (laughs), it’s amazing. I had this idea that the land and the sky were involved in this kind of congress, so rain is like some sort of arousal, and the way that trees grow is some sort of arousal. I thought that what I’d do was join the National Trust and take loads of photos of topiary and then make giant cocks out of chicken wire covered with astroturf. Then I planned to put the giant cocks into hedges and photograph them, and then photograph the sky separately, then rotate the sky by 90 degrees and have these cloud fannies with the trees and these astroturf cocks. I cycled miles around the south of England, photographing hedges and different sorts of grass.

I had a massive library of photographs, and then it was time to join Radiohead in the city of Los Angeles in the state of California, and it was great and we all arrived and had a drink probably, something like that, and then we retired to our opulent hotel, and there on the balcony overlooking the city lights, Thom says, “So what are you going to do for the artwork?” I said basically what I just said to you, and he said, “I’m not quite sure that that’s entirely appropriate.” So that was that idea fucked really. Over. After that I was a bit stuck for an idea, and as usual, I didn’t have a plan B. So the whole thing with Hail to the Thief happened sort of by accident. Because of the not being able to drive thing and LA being a car-based civilisation, I was always in the passenger seat of these vehicles, and I always have a notebook, so I was writing down stuff that I saw, all the signs: “Armed response,” “Turn left,” and there was a weird sort of Chinese symbol that said, “Ped Xing.” It took me fucking ages to work out that it meant pedestrian crossing. It seems obvious, but it’s not when you first see it. Who the fuck is Ped Xing? Is he a street artist?

Then I started realising after a while that because everyone in LA just drives a car, normally you’re going quite fast. So they’re not interested in subtlety or nuance or colour or anything. They don’t tend to use taupe, or teal, it’s brash colours: mental orange, or bright green, red, black, white, blue. There’s not more than seven colours that they use for the whole city, everything. So I used those, and the first paintings that I did were just of signs and stuff. And then I got back to the UK and of course the record wasn’t recorded in two weeks because that was just ridiculous with Radiohead. Thom gave me all the lyrics from the album and I cut them all up into tiny pieces and scattered them on the table and arranged them using the colours of Los Angeles and the technique of building a sort of canvas of real estate. So each of those was based on a map of a city that was somehow important in the War Against Terror. We had the city that I started in, the Pacific coast of Los Angeles, and I did a painting of Kabul, one of Grozny, one of I can’t remember, it was fuckin’ ages ago. So that’s the interesting and fun parts of the story of Hail to the Thief. And that was a series, each one of those was a metre and a half square. I spent the winter of the following year in a rat infested shed, painting.

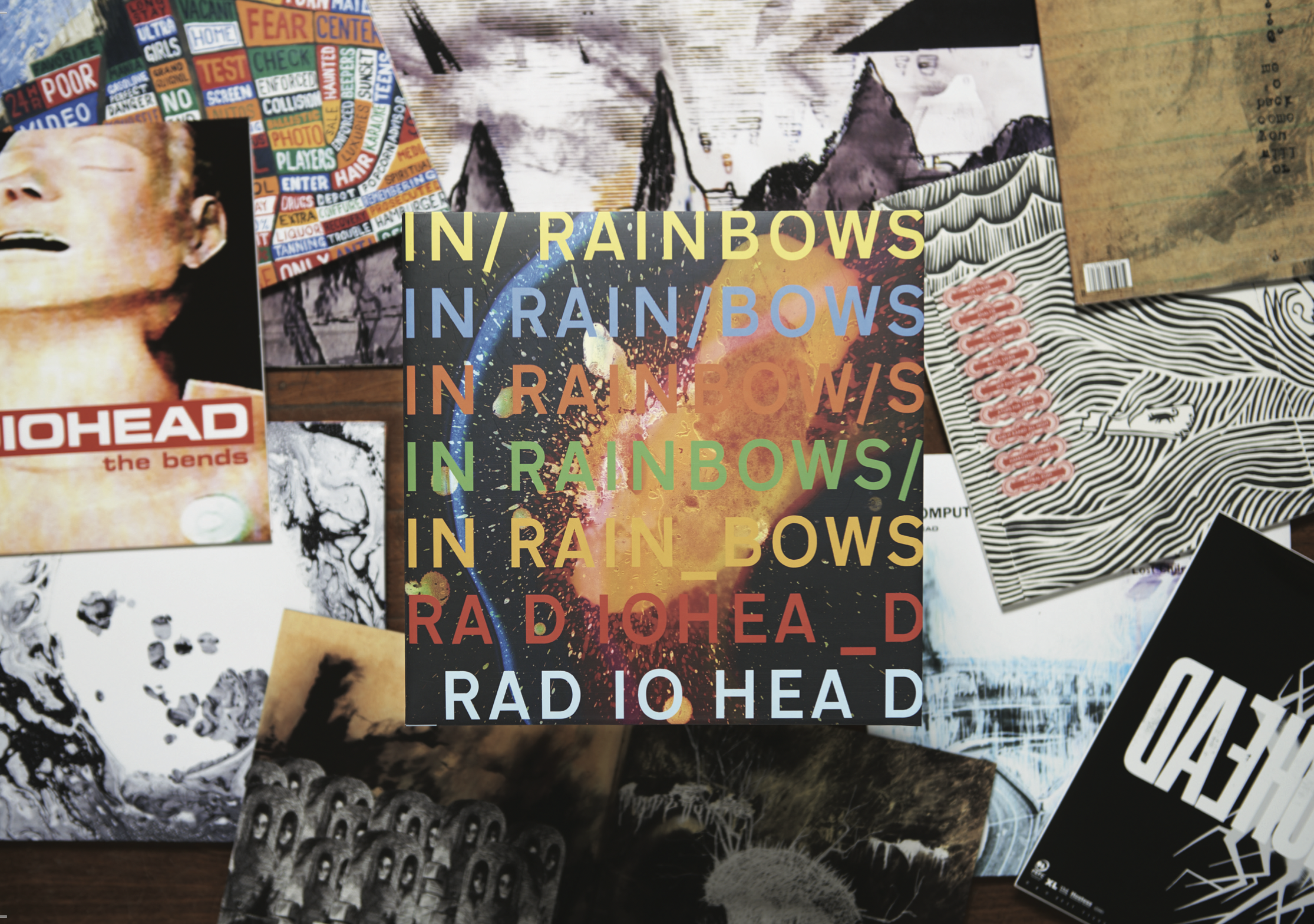

IN RAINBOWS

In Rainbows was great because we had total control over everything. The management had this crazy idea when they were playing golf or something—it’s not promising is it?—that the record industry was treating people that bought music kind of like criminals. And they thought, “Well, why don’t we not treat them like criminals and treat them as if they were honest?” So they had this idea that they would release the record and people could pay whatever they wanted for it. And as well as that, we’re going to do a boxset sort of thing—or rather, I am. Me, what?—that’s going to cost 40 quid. I was like, “What the fuck? You’re going to let people pay what they want for the record, and then you want me to design something that’s like a record sleeve, essentially, that’s worth 40 quid? You’re fucking having a laugh, man.”

This was before all the boxsets and collectors this and that, and a Pixies box that’s worth £1000 or whatever. So it was a real challenge because it was a big chunk of dosh. And then Ed (O’Brien—Radiohead guitarist) said, “Y’know, if you want to go and see a premiership football match it’s 40 quid easy.” And I was like, “Is it? Forty quid to watch a bunch of fucking idiots kick a ball around!” So we basically designed the In Rainbows record box from nothing. And I’m not really a product designer, so it was—what’s the cliché? —a steep learning curve. And many times I fell backwards along the curve, but in the end I was really quite pleased with the result. We made a big book that had records and CDs in it.

We rented this ridiculously decaying palace in the middle of a forest in Southern England, haunted by at least three things. No roof really, so when it rained it flooded, and there were stepping stones across this beautiful flooded hall to the only functioning toilet. It was too ramshackle to sleep in. The band were in caravans outside and I was in a tepee. The one dry part was the old library where they put all their recording equipment. I was working on an old school desk in the old school room of this place that was called Tottenham House. I had a bit of an accident in this old school room and I knocked one of the candles I used for illumination over onto the technical drawing.

To start with, I was like, “Fuck!” You can imagine when you’ve spent ages with a drawing board and a little fine pencil and stuff and then you knock over a candle and the whole thing’s fucked. But it was quite interesting because the wax was translucent, and where it had gone over the drawing—I don’t know what the effect is, like parallax or something—it looked like the line had come up and moved a little. It was really interesting. So I scanned it anyway, and that was really how I ended up doing the artwork. I did it with hypodermic needles and ink and wax. None of that actually exists anymore because it was incredibly fragile on paper, and the wax just breaks off. And I completely fucked a scanner with these wax things.

A friend of mine is a doctor, and I asked if he could get me any hypodermic needles. He gave me a whole bag in the school playground. That’s so dodgy, isn’t it? I would draw by putting the ink in them and then as you push the plunger down you can use the needle as a sort of nib. And it’s quite nice because it catches on the fibres of the paper, especially if you draw as if you’ve got some sort of nerve damage. You get these little spurts of ink. And then I went to the hilariously named Four Candles website and bought all this wax. I had all these cauldrons with all this wax bubbling away, and I was squirting ink out of the hypodermics and pouring like a sort of mad alchemist, it was great. And then I’d whack ’em in the scanner and do all the colour work in Photoshop with these images.

KING OF LIMBS

Since OK Computer I’d been doing a lot of paintings, big ones. The thing is, with all of these things it’s really hard because I always start off like I’ve got an idea that’s going to work, but then it is literally just an idea, and my total inability to do anything comes along a bit later. So with The King of Limbs—which wasn’t called The King of Limbs, again the titles are usually doing another record and we’ve never actually used any of the band’s pictures, their faces, in any artwork.” I’d recently come across the work of the German painter Gerhard Richter, he’s amazing. I’d seen these beautiful photographic oil paintings he’d done that were blurred, and I thought, “Ah interesting, oil paint, I’ve never used that before. Portraits of people in a photographic style, I’ve never done that before. Pictures of the band, I’ve never done that before. What could possibly go wrong?” And the answer is, everything.

So what I did to start with was I bought loads of oil paints (at considerable expense), bought loads of canvases, and got myself all set up. Then I got the band to sit down, got Colin (Greenwood—Radiohead bass player), who’s a very good photographer, to take photographs of all the band, and then I got the photographs printed out, took them into the studio, and then realised that I did not know how to use oil paints, or paint portraits, and that I was shit at everything. It was awful. I mean some of them started off ok, and I’d go in the next day and think, ah, and then I’d do something and the whole thing goes “pffft”. Oil paint is another thing that I can’t do. So what happened was I spiralled into the usual month of depression and self-hatred, “It’s all downhill from here,” “I’ll never have any ideas again,” “I need to get a job in Tesco’s stacking shelves because I don’t have any skills.”

It actually might have been even worse than the A Moon Shaped Pool depression which we’ll get to later, because in the A Moon Shaped Pool one I thought, “Well they’ve known me a little bit longer, they’re not going to sack me just like that. They’ll give me some sort of a warning or something.” But back then in 2011, I really thought I’d fucked it because all I had was oil paint and these brown canvases. They looked like dirty protests or something. It was so bad, and the music was going... I mean normally it’s a bit better because they’re having a bad time with the music, I’m having a bad time with the artwork, so we’ve got something to talk about when we’re eating. “Oh fucking terrible isn’t it, shall we give up? Oh go on then.” But the music was actually going quite well, and one miserable evening I wandered across the sodden field between their studio and my studio and sat down to listen to the wonders that they had made with music and technology and talent, and their studio’s this massive old barn with these curving timbers that go up right to the apex of the roof.

I was sitting there listening to the music, and they’ve got these beautiful speakers in the studio because if you’re a semi-popular rock ’n’ roll band, such as they are, then you tend to invest in some quite good speakers. Anyway, it sounded like being in a cathedral, and these great beams and rafters that come up in the converted barn, they’ve still got the nature of the tree about them, and I had this kind of vision that being surrounded by trees is essential to the religious, spiritual idea of our part of the world in our civilisation. Our cathedrals are like forest glades. They have these huge columns that are often fluted like the trunk of a tree, and they split into branches that become the stone tracery that holds up the roof.

And because I was seeing this incredible barn and listening to this incredible music—even a barn built in the olden days is a thing of beauty—I was thinking that before the Reformation all of the catholic churches were painted. I was thinking, “Imagine if they were all painted different colours, and if you went into the cathedral every column was a different colour that split into a different colour—it’d be amazing.” Then I was off back to my studio, and I painted over my brown paintings with oil again, and then if you don’t use solvent or anything and you don’t try to be clever you can just use them. So then I used acrylic, I used everything to make these multi-coloured trees and these huge forests and I used car spray paint to make black mist between the layers of trees. And that was the first time that I started drawing trees. Since then I’ve become addicted, and I can’t stop, they’re fucking easy man, trees are really easy to draw. Yeah, so then I started drawing lots of pictures and I started putting weird zoomorphic creatures in them, and trees, and voila.

A MOON SHAPED POOL

Before they started on the record, they were saying, “Ok, we’re going to make a record, France, going to go down there.” So me and Thom were talking about the artwork, and he said that he’d seen this documentary about this abstract painter who had un-stretched canvases and massive pots of paint, and basically just chucked them around, like a nutter. And apparently the results were brilliant. I thought that actually sounded like the sort of thing that I could do as it doesn’t actually require a lot of skill. So I was quite keen, but then I was like, “Ok, so how do you do, like, not exactly that.” I wanted to paint in an abstract way, but that’s a lot harder than it sounds because abstract art can be, well, it can be very difficult because it’s very easy to make it terrible. But you don’t actually know until you try, because you see, “Oh my god, that colour next to that colour is absolutely awful.”

I still wanted to do away with human agency, so I started experimenting here (at home in Bath) with water in what was essentially marbling. I bought loads of inks and loads of canvases and I had an idea that I was going to do this on a big scale, and here it seemed to work pretty well. I thought, “I can do this, I’ll upscale.” I bought all of this really nice American sign writing enamel and I bought a massive pond-liner and loads and loads of canvases. They all went in the back of a lorry and down to the south of France where I built this square pond. Right from the beginning it didn’t work, because of the wind down there. There’s a trade wind, the Mistral, that blows down from the mountains. It’s quite a warm wind, but it’s the wind that’s supposed to drive men mad. So the wind is blowing all the time, and if you try to do something on the water, it’s fucked, it’s gone. Then I thought, “Ok, I’ve got the studio, what can I do with a brush?” And I spent hours, days actually—two weeks solid painting this stuff, and it was not very good. At least I didn’t think so, and if I don’t think it’s very good then no one else is going to think that it’s very good. So I was really miserable, I thought I’d fucked it; “What have I done,

I’ve had my last idea obviously some time ago; my moment came and went without me being able to have a party or anything. I am now shit, I’ve done everything that I could ever do and it’s all downhill from here.” So I was really quite downcast by this, and angry, and maybe a bit depressed. And on top of all this, I don’t think the music was going very well either. But then we all had a week off. I got back, and there was this one there—amongst the 20 odd that I’d done—and it was like, “Fucking hell, that’s the one.” Essentially it was black and white and, the same old story, everything else was way overcomplicated. Strip everything back. I’ve got white canvases, I’ve got this incredible weather, I’ll just use black and white paint, and that was it. And so I just kept doing them. Then there was a mad thunderstorm, and that did something to the wet paint, and I basically did a week of that and it was just great. And the music was going brilliant over there, it was fucking ace man, we were going out for happy bike rides up mountains and nice things like that; it’s the long awaited happy album. So then we got everything back in the lorry and we went back to Oxfordshire and I carried on in their recording place there where I’ve got this lovely barn to work in. The weather, of course, was not really the south of France in September. So the ones that I did here (in the UK) were really different. They were a lot more sombre, somehow, than the ones that I did in France which were quite lovely. The one that I did that was on the front of A Moon Shaped Pool is from France. But some of the other stuff that’s inside is much more affected by rain and less affected by wind. In the end I ended up with 13 paintings, which I was pleased with. They’re all currently about to be shown in the the Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht, in this gallery that’s all painted black. They’re probably being put up now. I don’t think I can go, but I’ll go later. I’ve only seen them in barns and other messy environments, so seeing them in a museum will be like, “Wow!”