Studio: Alice Laura Palmer

I arrive in Redfern mid-morning and get lost immediately, I text Alice and we meet at a coffee shop a block from her studio when we walk back and enter her space it is sun-drenched.

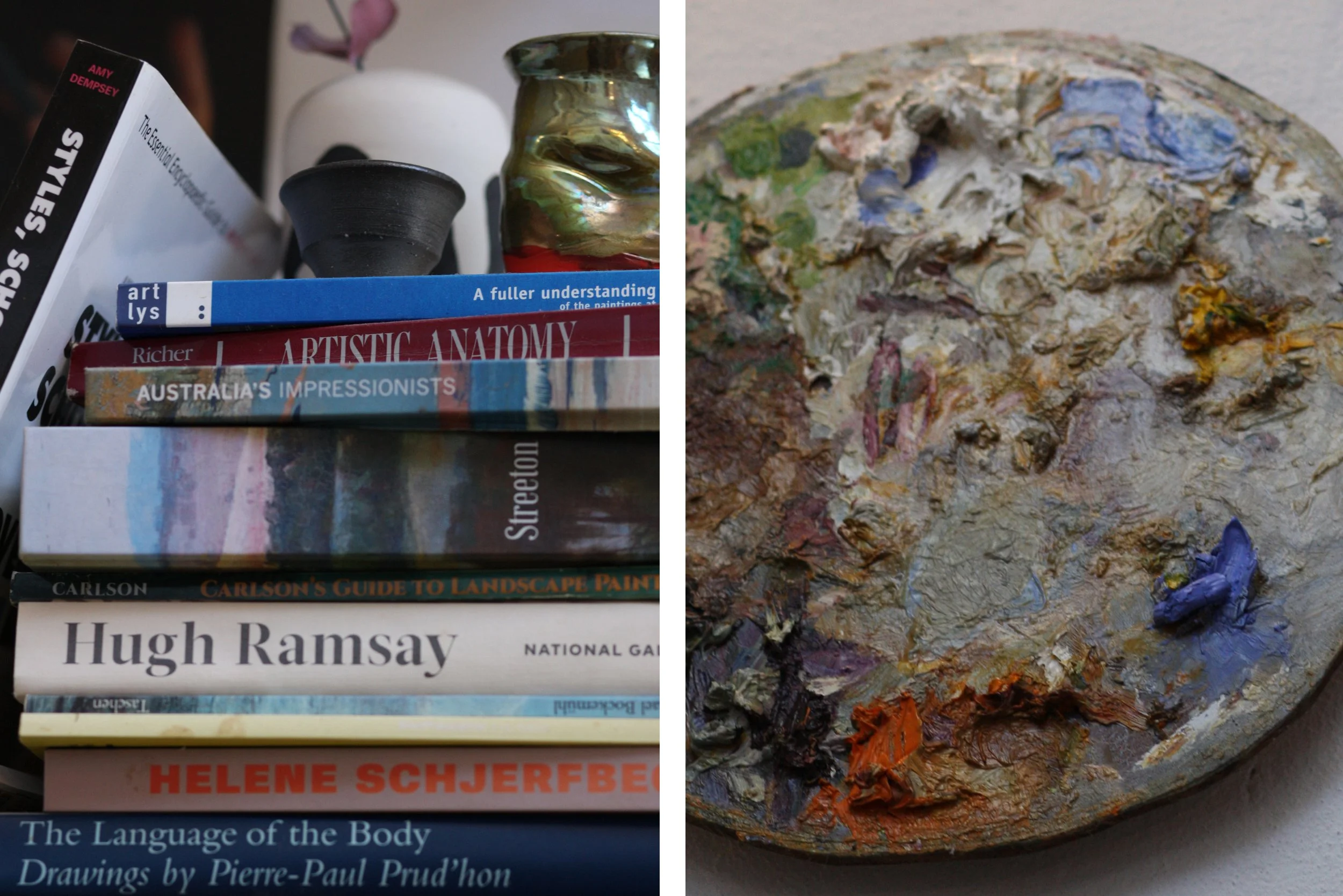

Alice Laura Palmer paints here. The light is exact. Because of it her work has settled into a cadence: consistent, unhurried, more prolific than at any earlier point in her life.

She wakes at varying hours, sometimes five, sometimes ten. A coffee is a must to start the day. Then she crosses the room, unwilling to let the morning hours slip. She spends the first part simply reading the light, adjusting the space until it aligns. Only then does the painting begin.

“This particular room is the reason I’ve produced so much work this year, more than ever before. The clarity of the light removes obstacles; it feels like painting downhill.”

Her path combines science and classical rigor. Early influences included zine culture and magazine illustration; she studied neuroscience at university while pursuing practical painting. At seventeen, a chance entry into the Florence Academy of Art changed everything. She saved for three years through multiple jobs, then trained intensively in Italy for another three, emerging with a firm technical foundation overlaid on a scientific mind.

She does not see painting as distinct from other thought processes. Her true strength lies in forging unexpected connectionsbetween a Brecht quote, a meal, cultural identity, and an untold story. “I don’t primarily think of myself as a painter; I make things as best I can with the thoughts I have. The medium isn’t the focus it’s the idea.”

Glasswork became necessary for certain pieces due to its distortion, lens effect, fragility, and poetic shattering qualities that aligned precisely with the story she needed to tell. Material choices surface gradually: “There’s no single moment of having an idea. I walk around the problem in my mind, and it bubbles up.”

Color is her sharpest tool, approached with a singer’s precision. “If I have any standout aptitude, it’s color similar to a singer’s pitch accuracy. Every color affects the body psychosomatically.” Oils allow layered, indirect painting glazing and scumbling that refract light to create a glow photographs cannot replicate. She mixes classical mediums herself for crystalline resonance. Changing daylight shifts a painting’s emotion entirely.

She reveres masters who transmit feeling directly: Van Eyck’s mirrored self-portrait, Van Dyck’s light-altered expressions, and above all Velázquez, whose pigment feels like “a time machine.” Her own work carries similar timelessness, driven by “clarity of observation” that echoes Dostoevsky, Beethoven, or Gareth Liddiard art so clear it is almost unbearable, yet makes everything briefly feel right.

In strong moments she disappears into flow: “When it’s going well, the painting arrives on its own like in a slipstream.” Every piece has a story she remembers fully intent rooted in color, form, presence, or philosophy. Selling brings pain “they feel like losing a child” though explaining the work in person softens the loss.

Portraits captivate her most: “Painting someone I’m obsessed with is like falling in love the good and bad sides. It’s chasing something I’ll never fully catch, but that’s the point.” The mouth remains the hardest part; Sargent called a portrait “a likeness with something wrong with the mouth.”

Inspiration flows from literature (more intimate than painting), film, and weekly gallery visits. Academic training taught her to solve compositional problems upfront, yet some discoveries like a hidden duck beneath layers happen on canvas. She regrets the loss of reading’s mental friction in an era of effortless tools: “I’m concerned about future dementia from lacking friction in thinking everything is frictionless now. We need challenge.”

Shakespeare’s Sonnet twenty nine speaks to her directly, its arc of despair to redemption mirroring the artist’s inner life. The studio shifts with her energy pristine and lucky when clear, less so amid commercial clutter. She now respects her monthly cycles: peak weeks yield two paintings a day; low ones one every three weeks. She protects high periods fiercely.

About 74% of the works around her feel finished. Oils tempt endless revision, but she increasingly preserves sketches for freshness and forces herself through overworked pieces to learn resilience.

Easy or hard-won, comparisons elude her; volume and distance decide what lasts. For 2026 she seeks refinement of her neural glass sculptures “more elaborate and beautifully executed” while elevating her entire practice across three upcoming art fairs. In this light-drenched space, clarity remains the pursuit.