Not Safe From Birds

Words by Ernie van Amstel.

I write this now, very tired and drunk.

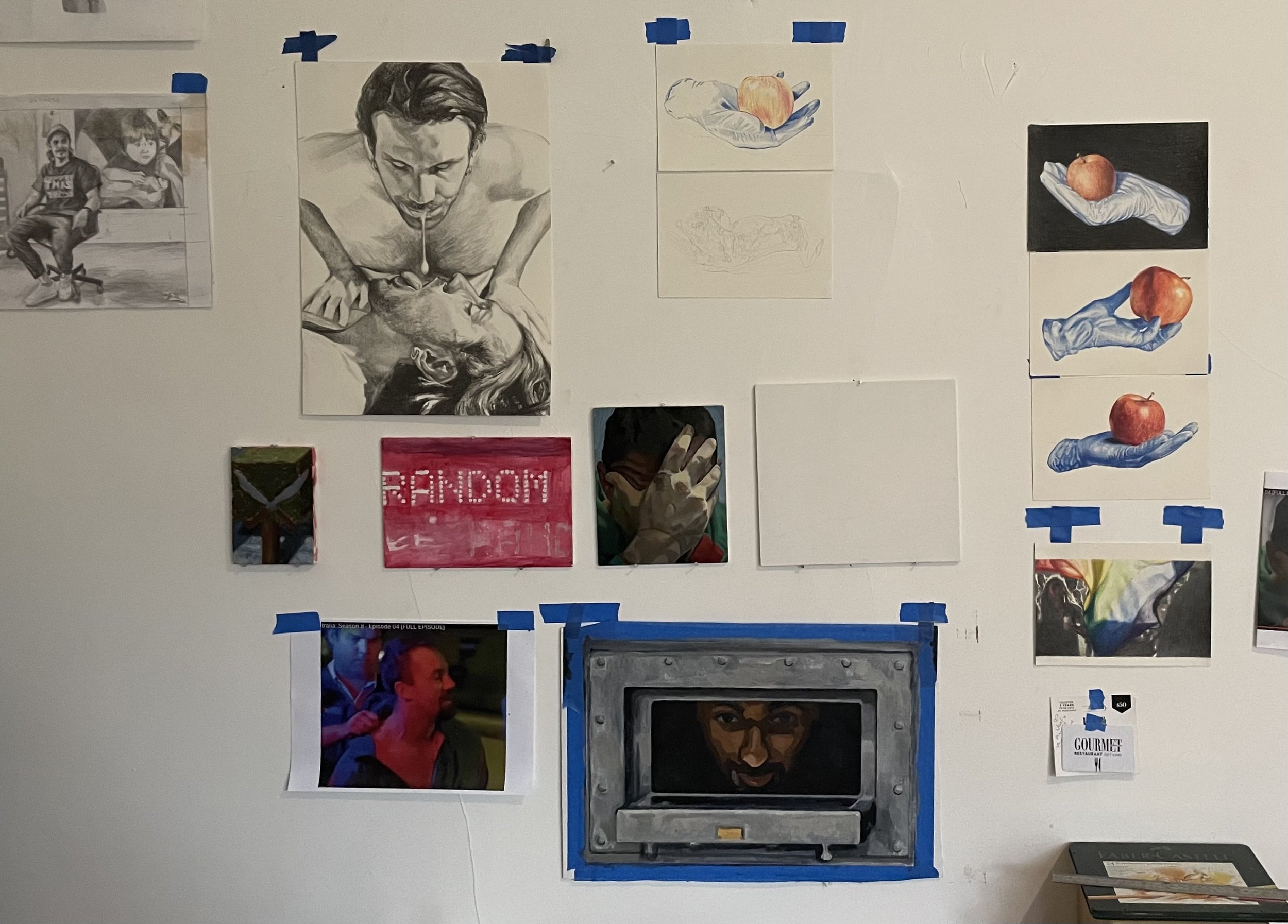

I have tried to write this piece a few times. I am bothering to write this at all because Shannon McCulloch’s work is very important. Art is what works. Beauty is what works. Shannon’s work is unflinching in its devotion to the less attractive, more interesting perimeters of life. His work shoots out of everything shaped and final, not in segments or sections. The work stands up to the flavours and preferences of present-day art culture, which seems to align itself with plain and splendid canvases: its bullies. This erosion of magical and romantic feelings into arbitrarily ‘good’ ones is something Shannon’s work is at odds with. The work is confessional, sensitive and dreamy. It sees something special in ordinary devastation. Through it, Shannon demures melancholia, placates gods, and pays attention to spiritual winters; a register of feeling I rarely see presented well, if at all—grimmer energies, beautiful ones, ones that work. When I look at Shannon’s painting, I can feel my heart fall open like a clam with a severed tendon.

It is well to explain to you here, that an inner diabolism often haunts the stalling culture we refer to as the Art World. I don’t particularly care for it. I wince when it’s vindictive behaviour flares up. Like most other great artists, Shannon McCulloch and every other artist I have ever written about is a fugitive of this world. When I think about it, it takes a certain kind of innocence to make adored artwork anyway. An innocence none of us can afford.

I’ve just now decided that I don’t want to write another single word about market, manipulation or vitriol. Instead, I will tell you some things about Shannon’s work that have stuck out in my mind.You know what they say: If you stare into the abyss long enough, it stares back at you. Shannon started staring in Perth a long time ago, and the jury’s still out on who has won the contest. His somewhat calcified affinity for secrets and corners and redactions is not new. In 2017 his installation titled ‘GREATEST HITS’ depicted surveillance camera-type CCTV headshots of pallid faces stalking around at night. It is a take on the West Australian newspaper that frequently splayed the words “GRAFFITI HIT LIST” on its front cover spread along with the comical and flattened headshots of “vandals caught red-handed in secret camera sting” on the Transperth train line. Many of them were not unknown to Mcculloch at the time.

So by the time he arrived in the cold, sprayed rubble of Melbourne to join its nascent art scene, McCulloch had developed a steady hand, an insubordinate sense of humour, and a flair for counter-culture. The work has always worked, even though it has changed many times over the years. I would recommend that everyone see it and no one ever tries to make anything like it.

Here’s one story: A long time ago, there was this guy called Zeuxis, a contemporary prodigy of the time; he was consumed by the idea of breaking away from traditional two-dimensional Greek painting and exploring depth. He made a fresco that changed the game. You can’t visit it or anything, it doesn’t exist anymore because it was destroyed. Destroyed by birds. Zeuxis had painted grapes that were so realistic, that birds flew into his fresco and pecked it into oblivion. It was “so successfully represented” that it was ravaged. If beauty is what works, it worked maybe too well.

I think of Zeuxis when I think of Shannon’s work sometimes. Not just because Shannon’s work is technically manicured, but because he too lacks cowardice, and his work tends to be pecked at and corroded by people. Someone called his work “possibly chromophobic” once, which is hilarious. His smudged-out inky blues and reds that glow like sirens give latitude to feelings that are somehow familiar and repressed, like he has plucked them from a black-out. Obviously joyous and colourful (chromophillic?) artworks have always been safe from birds. Safe from scrutiny. Shannon takes the initiative and has something to show for it. The work is stinging with life, and everything is given over to love.

For this reason, his work is not safe from birds. I’ll cherish it for as long as I can.