James Evans’ Invaluable Ephemera

Photos: Devon Blaskovich

The first time I kissed a girl, I bought a pack of Extra chewing gum so my breath would be okay.

I chewed one piece and then the rest of the pack rode around in my wallet untouched for years. It became a souvenir. This is true. And it’s also the gist of New York artist James Evans’ work.

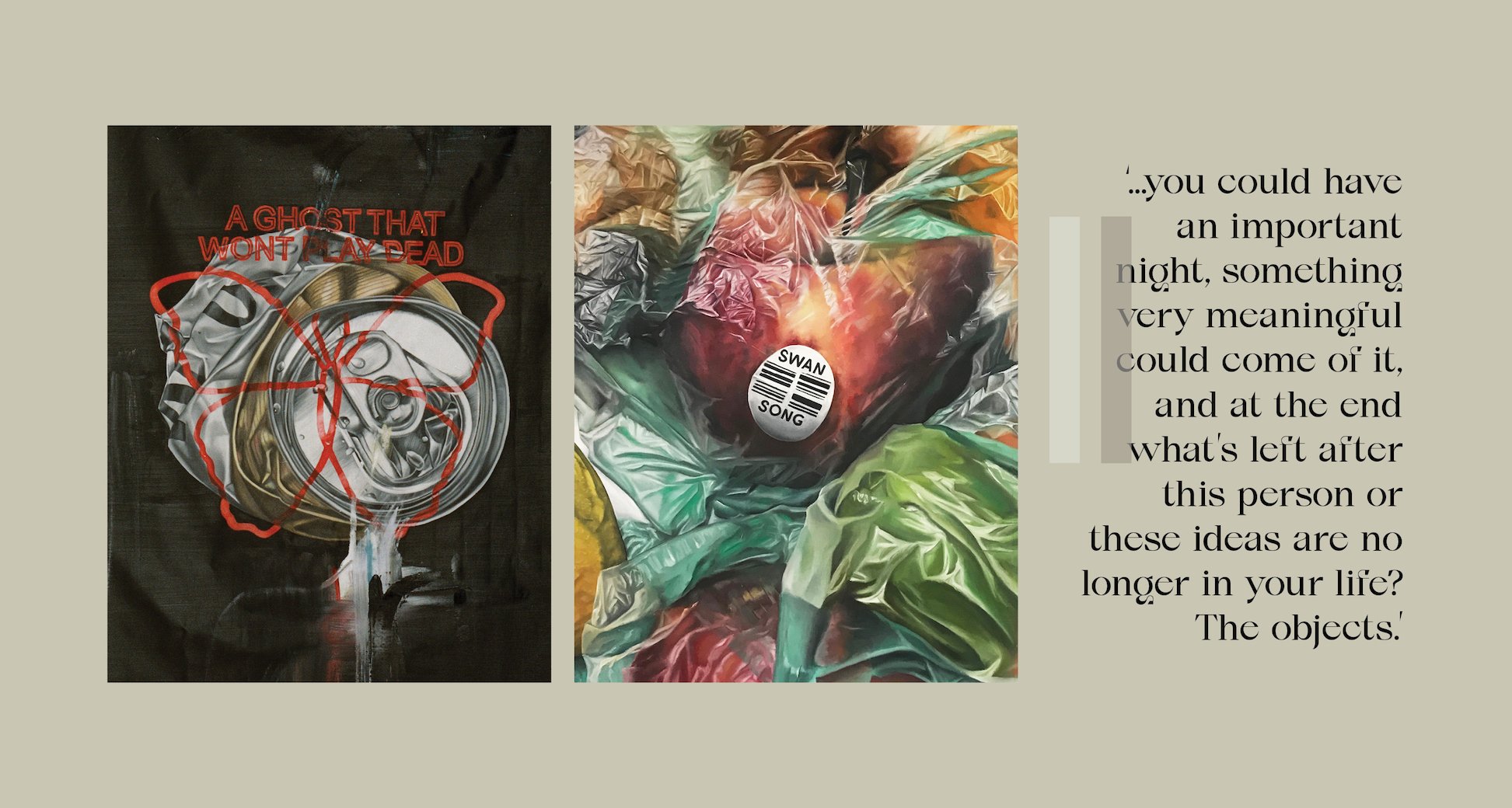

James paints those small, everyday objects that become imbued with great importance simply because they were present at a special moment. Beer cans, condom wrappers, pill jars; the peripheral props that happened to be there and so become nostalgic totems of his narrative. It’s very romantic, deeply sentimental, and a little heartbreaking in that James is trying to find a way to hold on to the past, or at least retain some proof that it existed.

Monster Children gave James a call the day after his solo show, Give Up the Ghost, in Mexico City to discuss impermanence and art’s role in the year 2020.

You’re in Mexico City right now?

Yeah. I just had a show down here actually, just last night. I’ve been down here on and off for probably eight months or so. I kind of wanted a break from New York. I felt like I was in a bit of a creative rut and I just kept hearing about Mexico City. So, I visited on a whim and it just clicked. It kind of made sense. And there’s a huge community of New Yorkers here. So, it’s been a nice back and forth. I’ve honestly had more stressful moves within New York than moving down here.

Are you from New York originally?

I actually grew up in Colorado, but I’ve been in New York for eight years and it’s always felt like home in a way that nowhere else ever really has. I always meet people down here [in Mexico] that are from New York and they’re always like, ‘Ah, fuck New York. I’m over it.’ And I’m like, ‘No, I still love New York.’ That’s still home for sure. But it’s just the kind of the nature of that city where you need a break from it periodically in order to get the most out of it.

Right on. Are you a full-time painter?

Yeah.

You went full-time recently, right?

Yeah, pretty recently. It’s been a really strange process, actually. I’ve never taken any art classes or anything. I actually went to school for writing, and then I moved to New York and worked in fashion. I was at Opening Ceremony for a while and Milk Studios, and then I started doing graphic design which led to digital illustration. Then I started working in advertising for a bit, and I started painting in my free time and it became an obsession. I would paint before work and after work and then I’d put on little shows around town.

So, you’re self-taught?

Yeah, yeah.

You’re a self-taught oil painter.

Yeah.

How did you get into it?

Well, when I lived in Colorado, I was just partying all the time and I had this really kind of destructive streak. And when I moved to New York I realised I needed something positive to occupy my time. I was just going through a lot of personal stuff. And so, when I had started as a graphic designer, I enjoyed the principles of design, but I was really tired of looking at a computer screen all the time. So, I just was like… well, I really want to learn painting. So, I would just paint circles and squares and shapes, and I did everything in acrylic and I would try to make them flat. And I would try to make the lines around shapes smooth, and I would adhere to a really small colour palette. I was really into Geoff McFetridge and Kaws and all that stuff at the time, and it was super derivative. Everything was vector-based, like here are some shapes and some forms and I would just try to make them smooth. But I would do this for hours and hours and hours because I was new to the city and I didn’t really know anyone. And eventually those forms went from being kind of knock offs of those artists, to being a little bit more figurative, and then to being more realistic and then eventually, acrylic just kind of became incorrect; I tried oil and that just changed everything. Like, suddenly these colours wanted to go together. And then from there, I started learning to sketch and stuff. But now it’s weird because the whole thing has happened incredibly backwards. And so also because of that, most of what I’ve done has been entirely outside of… I will have a couple of gallery shows this year, but up till now, everything has been entirely outside of the gallery model. It’s like I’m obsessed with this. It’s all I can do. And so, I just keep doing it, and eventually it just kind of starts to click.

And then you quit your regular job to paint full-time.

Yeah. I was in advertising and I was making decent money. It was a normal job, and I was like, ‘Fuck it. I am not happy doing this anymore, I just gotta paint.’ So, I quit, and I tried just painting for a while. But New York’s expensive, and I was going to fucking die. So, I took another job. Quit that. And then I got another one, but I was like, ‘This is my last job. I’m not doing this again.’ And then around that time, I’d developed a style that was starting to catch on a bit, so from there I was able to kind of make a living doing it.

Cool. How do you choose the objects that you paint? Are these things that are personal to you?

Yeah.

Like they have an ephemeral, souvenir type significance?

Exactly. That’s it. What fascinates me is we can have these moments… I’m really just interested in how things linger, how people and relationships and ideas come and go in our lives. And you can have a moment that is very significant, like, you’re out with someone and, whatever, you’re just getting drinks or something, but you could have an important night, something very meaningful could come of it, and at the end what’s left after this person or these ideas are no longer in your life? The objects. There’s still physical residue in the form of this object. And this object no longer has a purpose. It’s kind of useless. It’s trash, but it signifies a moment. And there’s something in between the signifier and the actual moment that I find really interesting.

That’s cool. I like that.

The stuff I did last year in New York was [based on] a lot of objects that were in my life at the time—grimy New York things like drug baggies and condom wrappers and beer cans—that was my environment at the time. But the whole point then is to add a narrative into that. And that’s where the graphic design comes into play, where I can recognise, okay, this is the typeface that was used on this condom wrapper or whatever. So, let me just split that and give it a message that I want it to signify. And then inverting that and giving it a purpose, even though it’s an object that its purpose has kind of ceased to be.

So, these pieces must be incredibly personal to you. Are they difficult to part with it when you sell?

Oh god, yeah.

Can you tell the story behind one of your paintings, like, what’s the story behind the Sapporo can painting?

I was in Tokyo with my ex, and I remember I was drinking a beer just walking down the street, and we had this really intense conversation. And at that point, I knew the relationship was over. This was a long relationship, and I held onto that beer can, and I brought it back to New York and I painted that. And that was kind of the first one that stuck with me.

I’ve seen that one; you’ve altered the text on the can. What does it say?

It’s a line from one of my favourite authors, Roberto Bolaño. It’s actually two different lines of his: ‘Every hundred feet the world changes’ and ‘Cheer up. It’s fun in the end.’ And obviously that can mean a wide range of things. But to me, it had a very specific meaning. So, there is that push and pull where you have that relationship with something and it’s strange to part with it. And also, it’s strange to keep making them and keep making them public, because for me a lot of these are very personal narratives.

But no one can really know their meaning without you explaining.

Right. They’re meant to be phrased broad enough that only I kind of get that part of it. But I want people to sense the emotional weight of something without having it explicitly say what it is. Because no one wants to be told… but a lot of these feelings are universal: excitement, fear, heartbreak, whatever. These are things we all feel. So, the point is to capture a feeling. It might mean something to me, but I want someone else to be able to feel their interpretation of that.

Have you noticed a shift in the idea of art and what it can and should be? Like, what role does art play in 2020?

I think a lot of it is that we just have such a barrage of shit that we see. There’s so much stimuli all the time. And that’s just more and more. And also, like advertising and stuff. We’re constantly surrounded by really creative things and really interesting things. And I think—to me at least—the role of art has shifted a bit, in that art has a responsibility to actually come from an important place, actually mean something and not simply be visually pleasing. Because we have enough things in our lives, and we don’t need more things. And so, if you’re going to bring something into this world, it should really mean something. Since I’ve got into this, I think that I’ve kind of felt more of that, more of a responsibility to make something that actually belongs in this world, something that has purpose, and it doesn’t really matter what medium that is. I think if you’re sincere in what you make, it’s going to come through. And that’s really my only litmus test for an artwork, is if you feel sincerity behind it. It could be a song; it could be movie. I don’t want to feel the hand of the author. I want something that doesn’t have pretension. And the beauty of art to me is in sharing something human. It’s like when you’re reading a book and you come across a line and it just stops you, right? You’re like, ‘Fuck. This is something I’ve always felt, and I’ve never articulated.’ And you just immediately feel this thing where it’s like, ‘Oh wow. This author’s on the same wavelength as me.’ I think about that a lot because I think as humans we’re all very connected. We all feel the same things. So, I think the duty of art is to share, and especially as the world’s growing increasingly xenophobic and just fearful, it’s important to share what makes us human.

That’s cool. It’s interesting you talked about not needing more stuff and yet there’s so much stuff coming into the world. In a way what you’re doing, because you’re painting everyday refuse and imbuing them with meaning, it is kind of recycling when you think about it.

Yeah, I mean, I don’t know. I’ve never really been able to wrap my head around things coming and going, like emotions or people or… I just can’t really… I don’t know. Certain things just linger. People have an impact on you, moments have an impact on you. And it’s this weird reality where especially I think it was because I was working in fashion for so long and things are so temporary. Like if you have, say, a statement piece from a season before or something, it’s suddenly obsolete a few months later. It’s just weird. The things we have in our lives, what of them are permanent? And the possibility that maybe something can be permanent and also still be ephemeral. Because we have these moments with people that we enjoy, we love, and we know they’re fleeting. And that’s okay. But they’ll have a permanent impact on us. For me, an object is like an interesting representation of that, because it’s so loaded. You see something from your childhood, you see something that reminds you of an ex or something and you just immediately feel something. And it’s triggered by this inanimate thing. Every now and then, I’ll tell myself, ‘Okay, I’m done painting objects.’ But I never am. They always creep back because they’re kind of the benchmarks of our lives in a really weird way.

See more from Issue 66 of Monster Children by picking up a copy here—we’re letting you decide how much you want to pay!