Issue 74: Model/Actriz

words by Austin eichler.

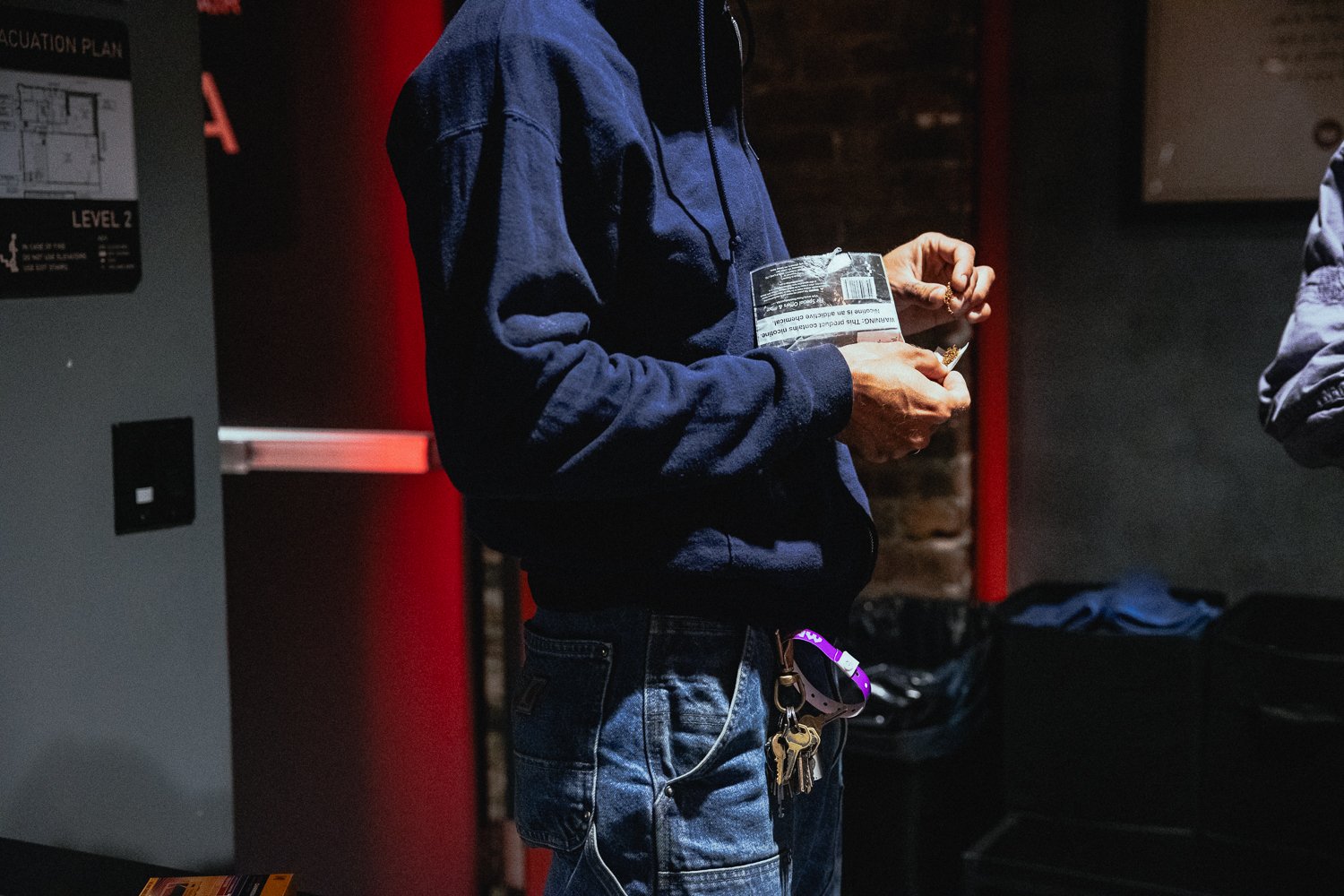

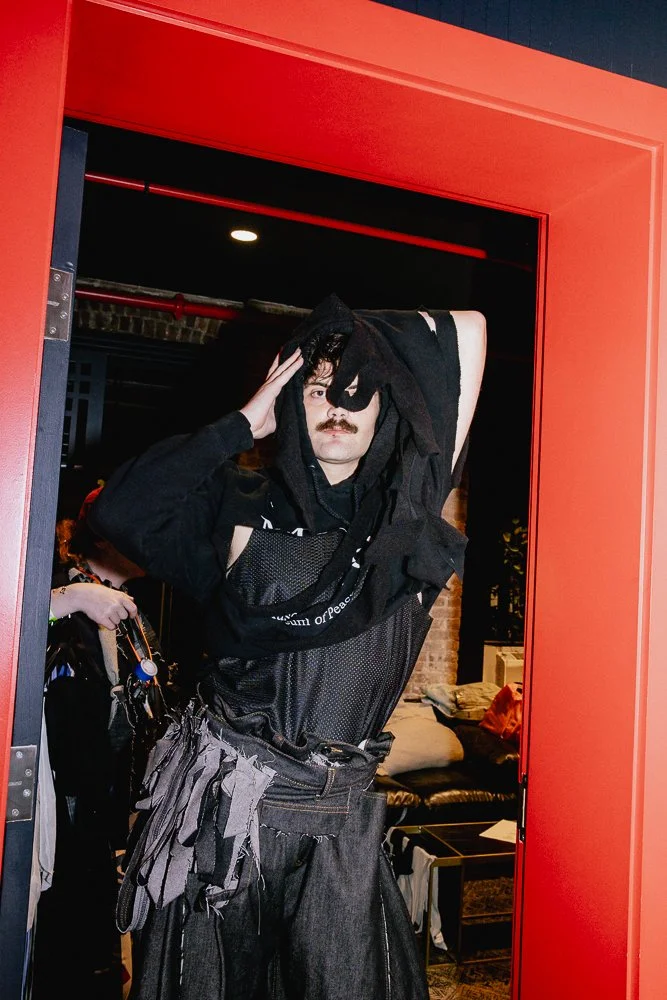

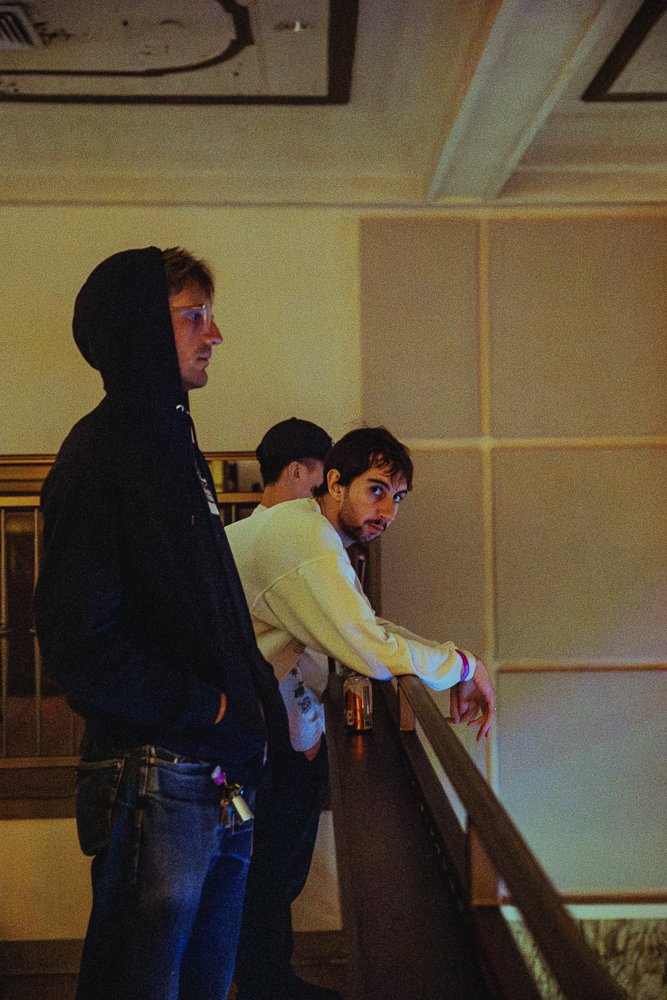

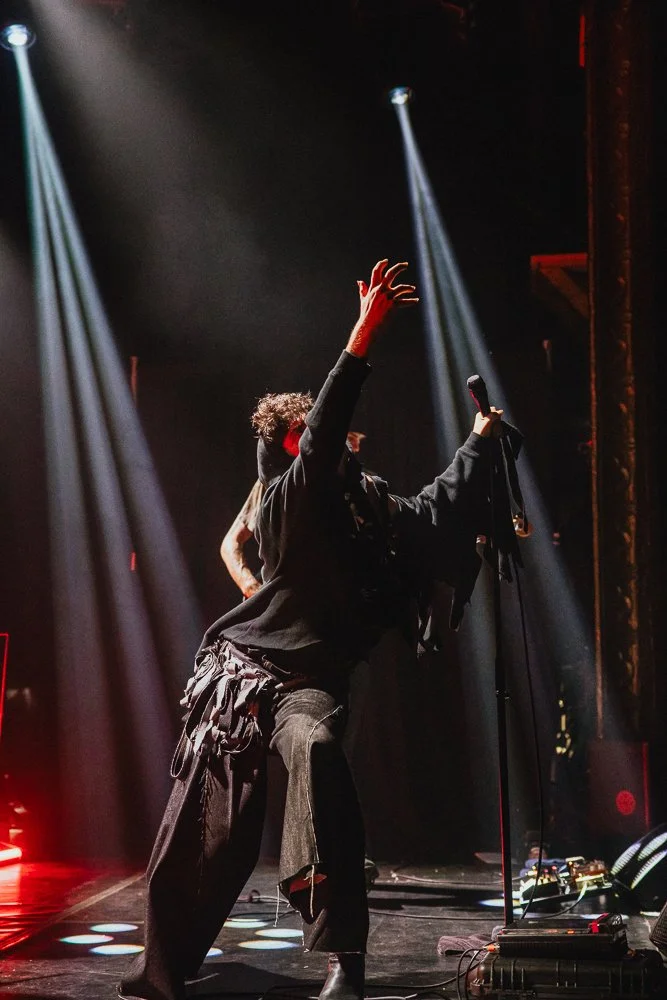

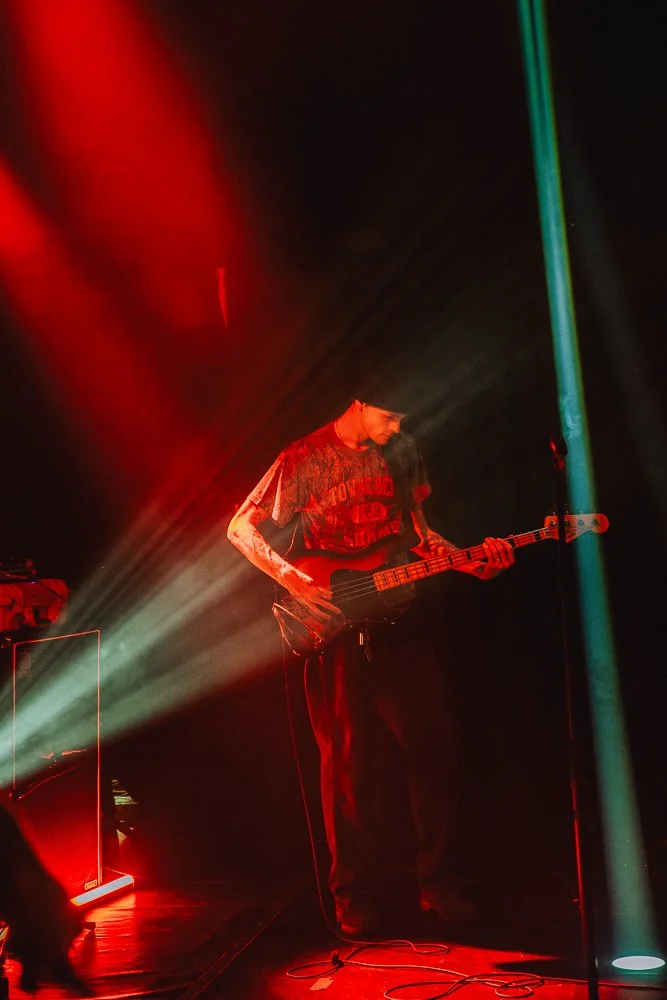

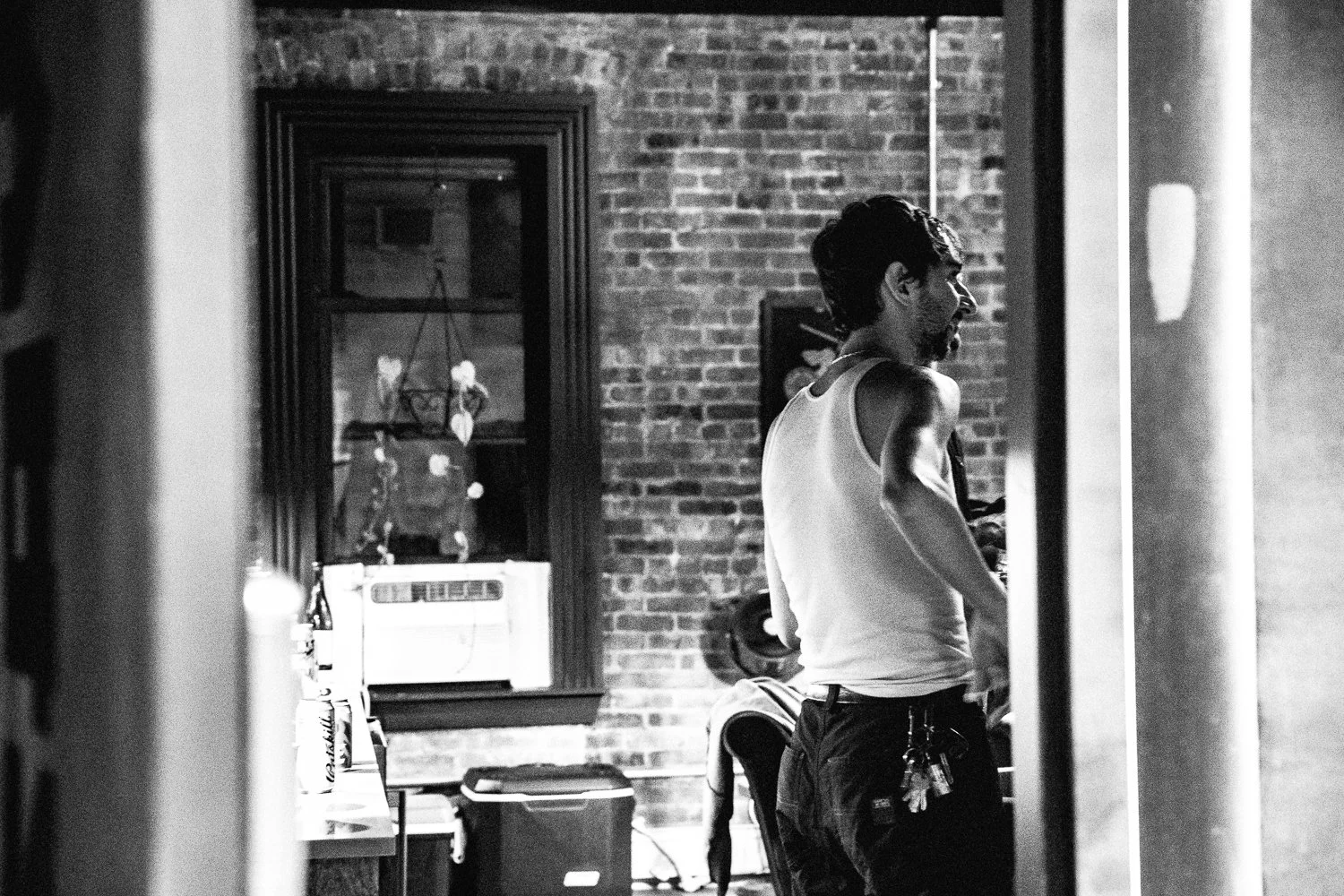

photography by Caroline Safran.

I first met Model/Actriz back in 2022 while on a tour with the both of us supporting the Los Angeles band Liily.

I’ve now seen Cole command a crowd of eleven hundred at Warsaw in New York City with the same fervor that he commanded a crowd of fifteen at a pizza spot in Pittsburgh (with an adjoining children’s birthday party to boot). I asked Jack about his pedal board once - I still haven’t a fucking clue how he’s making those sounds.

Model/Actriz cut through the whole of New York like a shard of glass dragged across flesh. Their music flourishes in that volatile space where the dance floor dissolves into raw abrasion, where movement feels as necessary as breathing. The live show unfolds almost as initiation: sweat, noise, and magnetic pulse merging into something communal and feverish. Brooklyn has no shortage of bands, but few can subjugate an audience with such ardor— ecstatic, unflinching, and perilously alive.

Model/Actriz remind us that liberation and annihilation are sometimes the same ecstatic scream.

[Model/Actriz is Ruben Radlauer; Jack Wetmore; Aaron Shapiro; Cole Haden]

Get your hands on issue 74, here.

CH: No more speculating about my age, we are on the record.

I mean, the speculation is that you’re young, like a teenager.

CH: I couldn’t move like that on stage if I were a teenager. Years of practice.

You seem like you’ve had moves. Were you a professional dancer or is this just time spent leisurely moving?

CH: I was never a professional dancer, but I was on the school dance team, which was maybe one of the most embarrassing things I’ve ever done because I did not really have that many friends in my high school, and I was like one of three gay kids, and being a gay kid who didn’t have that many friends - in high school, having to perform at the school pep rally was the most embarrassing thing. It was the worst feeling in the world, because the pep rally is a performance that you do with the lights on; I have to look at the fucking people who are calling me gay in the front row.

Did you not sign up for that?

CH: I was born this way.

[Laughs]

CH: I mean what class is a gay guy supposed to take if not advanced dance?

AS: They found out you were gay and were like, ‘you can skip beginner dance’.

CH: Yeah, and because I knew how to tap dance.

I didn’t know anybody knew how to tap.

CH: I have my tap shoes but I had to take the laces out of them to use in another shoe.

You’re a very engaging band to see live. There’s a lot of contrast between Cole and the rest of the band. What do you all think that you bring to your live performances and how much care or thought do you put into that beforehand?

CH: I think I’ve meditated on the mood and emotional storyline that I want to come across, but it’s never choreographed. I think I want to invoke a sense of controlled chaos.

JW: We all come from different backgrounds in music and our stage presence comes from those zones. Aaron and I grew up in hardcore, that’s our vibe. Cole growing in pep rallies-

CH: And theatre.

JW: It’s not premeditated, it’s more of a vibe.

Are you aware of your clash? Even when Cole gets into the crowd, there’s still a lot to see on stage. Was that ever a conversation you had?

CH: It wasn’t a conversation that I had - I didn’t really ask if they were even okay with me going into the audience, it was just something that I needed to do. Maybe they’re less forthcoming about it than I am, but I’ve always seen their own flare for theatrics. Even if I’m not on stage, the show continues on stage. When you can see what's going on and the lights aren't too dark, you can really sink your teeth into the way that the music is entirely made through humans despite aesthetically sounding like it’s being sequenced through machines, and I think that the amount of discipline and rigor in our sets are just as intense and important as my own kind of flamboyance and… unhinged-ness. They are opposite but very much apparent in our shows.

RR: In a lot of ways, I feel like my role as a drummer is to be the signal of the kinetic energy of the band, and a lot of the music we reference is dance music, so sonically it makes sense to use drum tracks, but it feels that the live aspect and motion - the air moving is really a thing that drives energy into all of us. Less so the keeping of time, and more the keeping of sonic energy… the wind.

The wind keeper.

CH: I said we were like water earlier, we are a very elemental band.

Super elemental.

AS: It’s kind of like how when you see a really good DJ, the thing they’re doing isn’t very involved, but you can feel the energy and that can be very infectious for a crowd. Like when I see a really good DJ, they might not have done shit for a few minutes, but they still command the audience. A lot of what we do and think about is in terms of crowd participation, and wanting to give those signals to a crowd that you can dance - you can make this show whatever you want it to be. Sometimes people just need permission.

You are all from different backgrounds, hardcore and theatre, what do you like in a show?

CH: Because you said ‘hardcore’ I checked out and waited for someone else to talk.

JW: I like seeing full chaos on stage, it pulls me in when I can’t tell exactly what's going on.

CH: Is that why you’re partial to the Manchester show?

JW: It was insane. There were like a hundred people on stage.

CH: It speaks to the difference in our mindset. I was definitely there for people to be chaotic, but I wanted people to use it like a catwalk or a runway.

Even if it's not choreographed, it feels like chaos with intent.

CH: I’ve never said this outloud, but there are moves that I do every show because I’m waiting for someone to notice and do them with me.

Like what? And when?

CH: The chorus of ‘Slate’, always the same. I do a drop and pat my ass during ‘Crossing Guard’. Recently I’ve been doing high kicks at the end of ‘Mosquito’ but I don’t expect anyone to do that. It’s hard in a crowd.

Your last two albums were very different. What was the biggest challenge in writing those songs?

AS: On Dogsbody, we were going through a lot and in a big transition for all of us in our lives, but the music felt like we were writing good shit and it was coming very quickly. We were transitioning into real adulthood, versus in Pirouette, we were all in the professional touring band mode, where the struggles had to do with the opposite, where everything is going well.

Did you just throw a soccer ball?

AS: Hell yeah. I’m a pillar of this community.

CH: Lyrically, I agree with you, Aaron. The experiences that accumulated between the albums were mostly clubs. It was at Primavera that Brat came out, which was what unlocked things for me. That’s like a club diva album but also about insecurities. It was inspiring, the emotional palette.

RR: I agree with that in a sense. We wanted to make a tonally brighter album. On Dogsbody, we were trying to make a heavy album and using a lot of the palette of heavy music, but with Pirouette, we were using the same compositional techniques but trying to use club and pop music.

Interesting. To me, Pirouette sounds more sinister. Is Brat scary? Maybe.

CH: Not to be like, shoot for the moon and land among the stars, but maybe you shoot for Brat and you get sinister, too. I think Pirouette is not quieter, but it has more poise, and is less anxious. I think that Dogsbody is the mentality of a victim, and Pirouette is… I don’t want to say predator, but calm, because a person in power is calm.

Confidence is scary.

CH: Yeah, so I can see what you’re getting from it.

How are you handling success? You’re playing late night shows, you tour a lot selling out shows; are you okay?

AS: We talk about this amongst ourselves, but I remember being a teenager and wanting to be in a big successful band and thinking that I needed to do that by the time I was like twenty three, and now that things are popping off for us, and I’m thirty, thinking about being a twenty three year old and having to do all of this stuff is crazy to me. We’ve had to put a lot of work and mental space into relationships and molding things around what is an unconventional work schedule.

RR: We are ourselves, which you can’t always say. We would like to be more successful, but at this level, we are ourselves.

AS: You can be an unsuccessful band that tours six months out of the year, and your life is more similar to a successful band than a poppin ass artist who doesn't tour. Touring is really intense and it's awesome all the opportunities that we are getting, but in general being on the road is really intense.

RR: There’s a weird disconnect between what looks like success on paper and how successful you have to be in this industry to be approaching middle class. It’s interesting just kind of cracking that. It feels like we have to do exactly this forever or the rug gets pulled, and on one hand it’s awesome to have some success, but on the other just seeing the fragility of the industry is scary.

AS: There really is no middle class in music anymore. You get to the point where you can get by and it's incredible, but it really feels like the next few kinds of ceilings you have to push through historically are like buying a home, and that doesn’t really exist anymore.

CH: You have to pop off on TikTok.

Apart from finance, would you like to change? For example, I want more shit talking in music, what do you think would be a good thing to change or steer your culture and industry toward?

RR: I like your idea, more shit talking in music.

CH: Yeah I like that.

AS: More call outs of the shit that everyone experiences that sucks in a way thats not ‘fuck this person’, but a way that is purely about raising awareness so that when people are in similar situations, they have knowledge and resources. We don’t need to cancel anything, just like contracts or… I hope that pay-to-play shows aren’t a thing anymore, but I didn’t know that there was a term for this toxic thing in the scene. I didn’t know it for years but then realized that I was doing that when I was nineteen, I would hope that there’s an understanding now that people shouldn't be doing that. It’s really hard to steer through a local scene without handholding, but there are a lot of bad actors and scary people.

RR: The biggest thing that would immediately benefit the scene would be monopolies getting broken up. Power and money get consolidated at the top and it eats into artist’s livelihoods. It’s a buyers market and I feel like artists will do what they do for free because it’s what we do. It’s been glamorized, the starving artist thing. Also, the ‘grindset’ where people just accept nothing. I think that universal basic income and healthcare would be a helpful thing.

AS: I was listening to this podcast about these changes that are coming to the structure of pay in the NBA, and the eradication of the middle class of NBA players, and I was like bro even these millionaires have to deal with this, and if these top athletes have to deal with this, what hope is there for the local scene?

RR: What we need is a revolution.

CH: I want to see laundry machines in every venue in America. And everything else everyone else said. Healthcare would be amazing. The insurance I have only works in New York City, so every time we get in that car I’m like, put me in the bubble I cannot get sick I will never financially recover from needing stitches.

Are there any parting words?

AS: Hi, mom.

RR: We need people in positions of power taking more risks on art. The people yearn for something different.

CH: Alex Warren does not deserve to win VMA’s.

RR: Yeah.